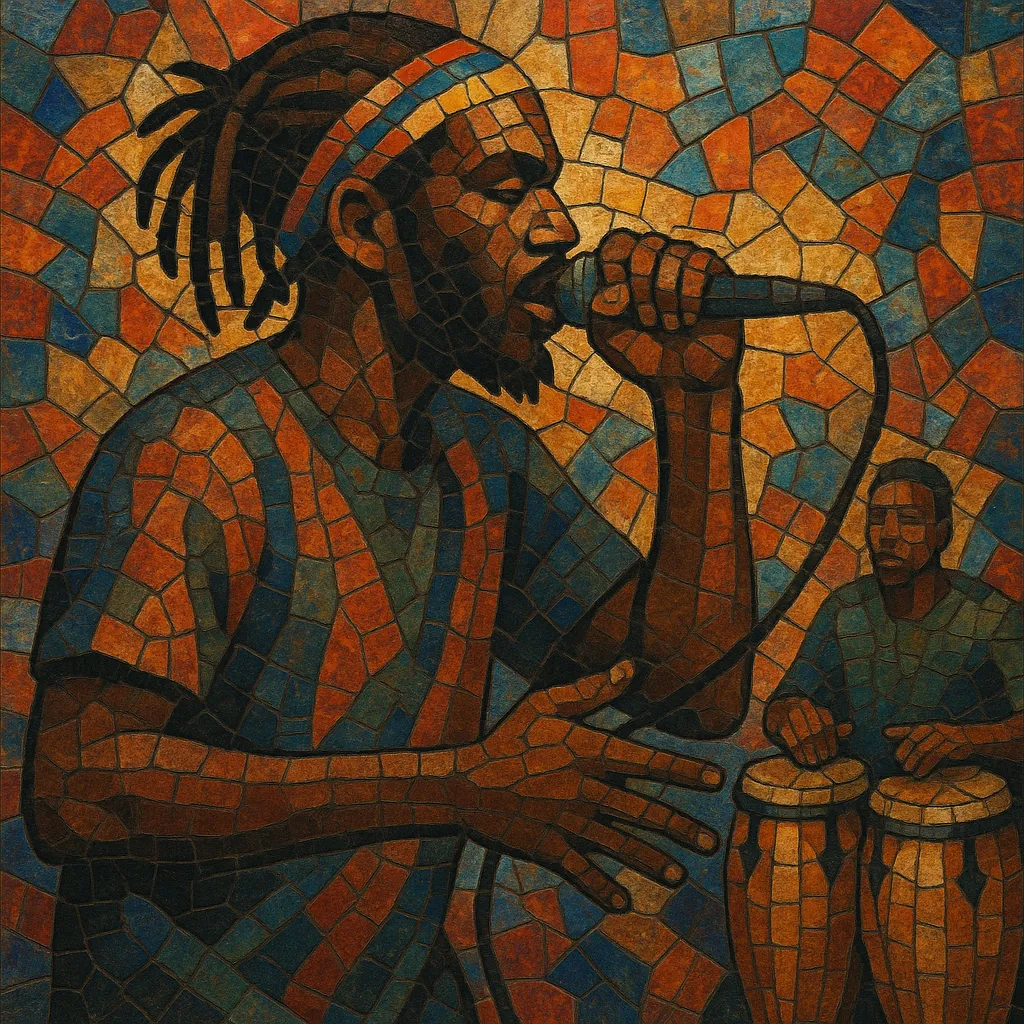

Rapso is a Trinidad and Tobago genre that fuses calypso and soca rhythms with spoken, chanted, and rapped vocals rooted in Caribbean oral poetry. Emerging in the 1970s, it centers the “power of the word” over groove-heavy percussion, call-and-response hooks, and Carnival street energy.

Unlike American rap, rapso developed from calypso’s chantwell tradition and the island’s protest poetry, then absorbed elements of hip hop as both forms evolved in parallel. The result is socially conscious, rhythm-forward music that can move a Carnival crowd while delivering pointed commentary in Trinidadian Creole.

Rapso took shape in Trinidad and Tobago in the 1970s as artists experimented with delivering poetic, socially engaged lyrics over calypso and emerging soca rhythms. Pioneers such as Lancelot Layne began pairing chant-like delivery and conversational rhyme with local grooves, placing narrative and critique at the center of Carnival-ready music.

In the 1980s, performers including Brother Resistance helped formalize rapso’s identity. The movement emphasized the "power of the word"—the idea that speech and rhythm combined could educate, agitate, and uplift. Groups like the Network Riddum Band brought hand percussion, drum-set soca patterns, and chant choruses to stages and street processions, asserting rapso as a distinct voice within Trinidadian popular music.

The 1990s saw increased visibility through acts such as 3Canal, who fused rapso’s spoken delivery with big, chantable hooks suited to J’Ouvert and Carnival. Artists like Ataklan and Kindred broadened the palette, mixing rapso with modern production, reggae, and soul, while maintaining its core commitment to social observation and local storytelling.

Rapso continues to evolve alongside soca and Caribbean hip hop, influencing how Trinbagonian artists frame political commentary, identity, and Carnival culture. Although often underground relative to mainstream soca, rapso remains a respected vehicle for protest poetry, cultural pride, and community expression.