Ponto de Umbanda is the body of liturgical songs used in Umbanda, an Afro-Brazilian religion founded in the early 20th century. Sung in Portuguese (with occasional African-derived words), these short refrains are performed to invoke, praise, and guide spiritual entities such as Caboclos, Pretos-Velhos, Crianças, Exus, and Pombagiras.

Musically, pontos are call-and-response chants accompanied by sacred drum patterns (toques) on atabaques, handclaps, and small percussion. Their rhythm and tempo shift according to the spirit line being worked: slow and tender for Pretos-Velhos, medium and swaying for Caboclos and Iemanjá, and faster, more incisive grooves for Exu and Ogum.

As a devotional practice, ponto de Umbanda is inseparable from ceremony: the songs structure the ritual, help establish trance, and mark the entry, movement, and farewell of the entities. Beyond the terreiro, pontos have periodically reached the public sphere through recordings and stage adaptations by Brazilian artists, preserving their core call-and-response energy while translating sacred rhythms to concert settings.

Umbanda emerged in Rio de Janeiro in 1908, synthesizing African (Yorùbá and Bantu), Indigenous, and European (particularly Kardecist Spiritism and Catholic) elements. Within this religious matrix, ponto de Umbanda took shape as the sung, participatory language of ritual. It inherited call-and-response structures and drum-led grooves from Afro-Brazilian practices and adapted them to Umbanda’s distinct pantheon and liturgical flow.

Through the 1930s–1960s, terreiros across southeastern Brazil codified repertoires for each “linha” (spirit line), aligning specific toques (e.g., congo, cabula, ijexá) with appropriate tempos, texts, and spiritual functions. The three atabaques—rum (low), rumpi (middle), and lê (high)—and support percussion became standard, with ogãs (ritual drummers/cantors) leading responsorial singing that guided trance and procession.

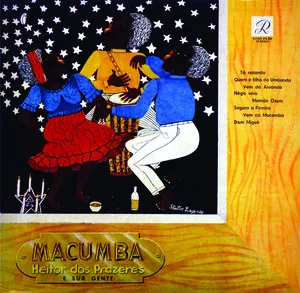

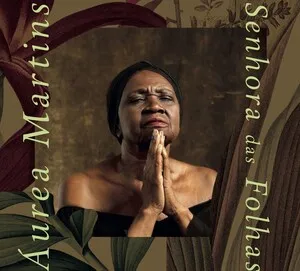

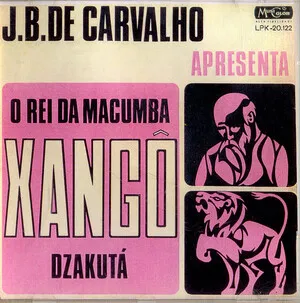

From the 1960s onward, recordings labeled as “pontos de macumba” or “pontos de Umbanda” circulated on radio and vinyl, sometimes exotified, sometimes reverent. In parallel, major Brazilian artists—especially within samba and MPB—adapted or referenced pontos and ijexá/congo feels, bringing sacred melodic turns and refrains to concert audiences while acknowledging their religious origin.

Since the 2000s, community choirs, terreiros, and cultural projects have documented pontos via CDs, YouTube, and archival initiatives. Workshops for ogãs and cantoras help pass on toque technique, repertoire, and ritual etiquette. While creative adaptations exist outside the terreiro, practitioners emphasize respect: in sacred contexts, pontos remain functional music—songs that serve spiritual work, not mere performance pieces.