Piedmont blues (often called East Coast blues) is an acoustic blues style from the U.S. Piedmont region (Virginia and the Carolinas down to Georgia) characterized by syncopated, ragtime-derived fingerpicking on steel‑string guitar.

Its hallmark is an alternating-thumb bass that keeps a steady 2- or 4-beat “boom‑chick” pulse while the fingers play off‑beat treble melodies, runs, and chordal syncopations on top. Compared with Delta blues, it sounds lighter, more danceable, and closer to ragtime and early popular song.

Lyrics range from humorous and risqué double entendres to travel, work, love, and spiritual themes. Performances are frequently solo guitar-and-voice, sometimes augmented by harmonica, second guitar, or small string‑band textures.

Piedmont blues emerged in African American communities along the U.S. East Coast, especially in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Musicians blended rural country blues song forms with the syncopated stride and cakewalk feel of ragtime, adapting piano rhythms to guitar with an alternating-thumb technique. Street performances, house parties, and dance halls helped codify the style well before it was extensively recorded.

The late 1920s and 1930s saw a wave of recordings that defined the style’s sound. Blind Boy Fuller’s prolific sides popularized the brisk, ragtime-inflected approach; Reverend Gary Davis fused virtuosic gospel and blues guitar; Blind Willie McTell brought 12‑string sparkle and narrative balladry. These records circulated widely, shaping the technique and repertoire for other players across the region.

After World War II, changing tastes and urban migration shifted blues toward electrified bands. The Piedmont approach persisted in local scenes and on records by artists like Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, whose guitar–harmonica duo projected the style to new audiences, while Josh White’s sophisticated phrasing bridged folk, pop, and blues markets.

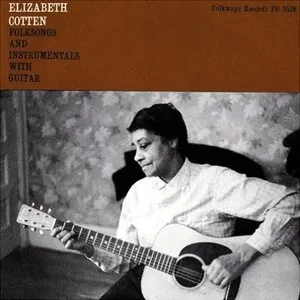

The 1960s folk revival rediscovered and celebrated many Piedmont artists. Elizabeth Cotten and Etta Baker inspired a generation of fingerstyle players; John Jackson and others carried the torch at festivals and workshops. Folklorists, guitar instruction books, and college coffeehouses embedded Piedmont technique into the broader acoustic fingerstyle canon.

The style’s alternating-bass vocabulary became foundational for American fingerpicking. Teachers, festivals, and archival reissues preserved the repertoire, while contemporary players integrate Piedmont syncopation into folk, singer‑songwriter, and roots music. Its approachable, danceable feel and intricate right‑hand patterns continue to define a living tradition.