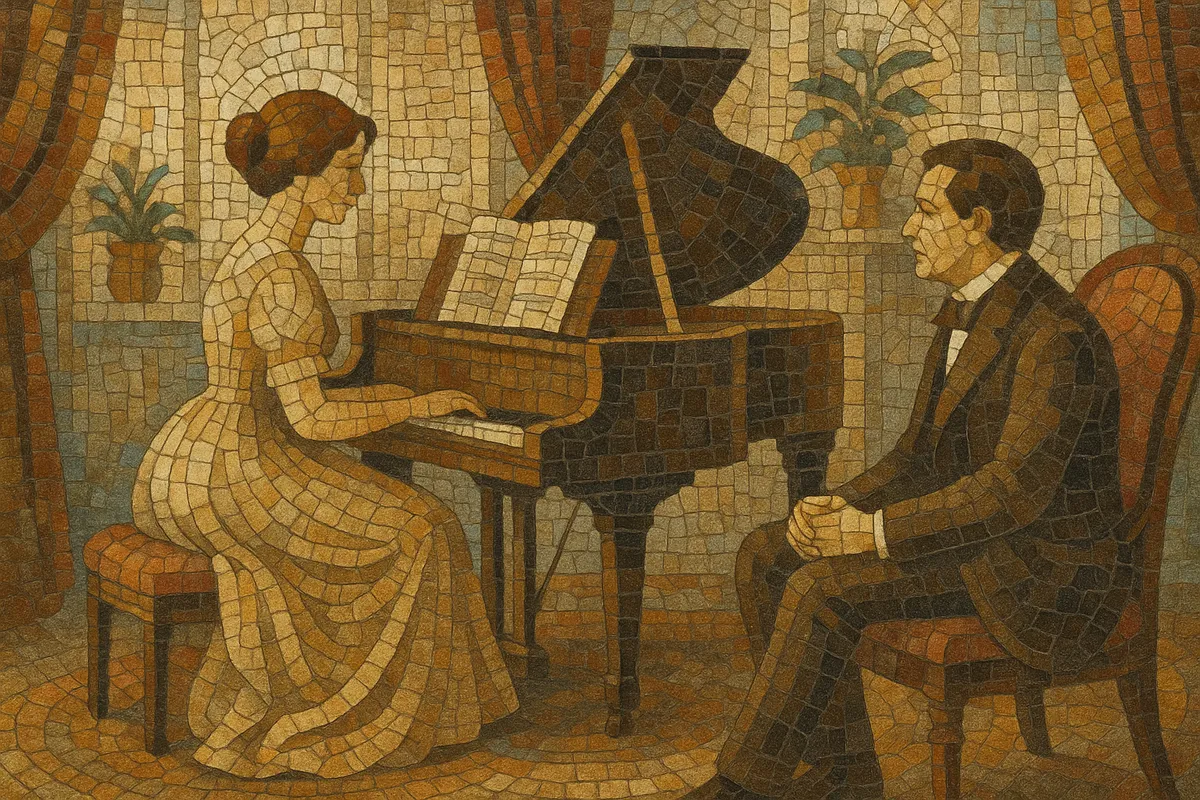

Parlour music is a 19th‑century popular style written for amateur performance in the home, typically in the domestic “parlour” of middle‑class households. It centers on singable melodies with piano accompaniment and was disseminated primarily through inexpensive sheet music rather than professional concert culture.

Musically it favors strophic or verse‑chorus song forms, simple diatonic harmony with occasional tonic–dominant–subdominant motion, and pianistic textures such as arpeggios, Alberti bass, and oom‑pah patterns. Themes are sentimental and domestic—love, home, faith, nostalgia, and bereavement—and the pieces are designed to be technically attainable, emotionally expressive, and socially suitable for mixed‑ability performers.

Parlour music emerged in the Victorian era as upright pianos and affordable sheet music entered middle‑class homes in the United Kingdom (and soon the United States). It drew on Romantic salon aesthetics, European art song, folk and ballad traditions, church hymnody, and the melodic sensibility of opera arias. Publishers marketed “songs for the parlour” specifically for amateurs—often women—who were increasingly encouraged to cultivate music‑making as a social grace.

The genre flourished alongside rapid growth in music publishing, with songsters and periodicals circulating widely. In Britain, sentimental ballads and drawing‑room pieces became staples; in the United States, composers such as Stephen Foster popularized parlor songs that blended ballad idioms with minstrel‑era and folk influences. Typical numbers featured clear verse‑refrain structures, memorable melodies in comfortable vocal ranges, and piano accompaniments that sounded rich yet remained playable at home.

By the late 19th century, parlour music overlapped with emerging Tin Pan Alley practices, music‑hall/vaudeville repertoires, and early recording. Big sellers like “After the Ball” demonstrated how the parlour song could scale from the home to the stage and the phonograph. As professional entertainment, radio, and records eclipsed domestic music‑making, the parlour style gradually morphed into early 20th‑century popular song and traditional pop standards.

Parlour music helped codify the sentimental ballad, the verse‑chorus song with piano support, and domestic amateur performance as a cultural norm. Its melodic clarity and accessible harmony fed directly into Tin Pan Alley, traditional pop, and the modern singer‑songwriter tradition, while its piano textures and lyrical themes remained templates for intimate popular song for decades.