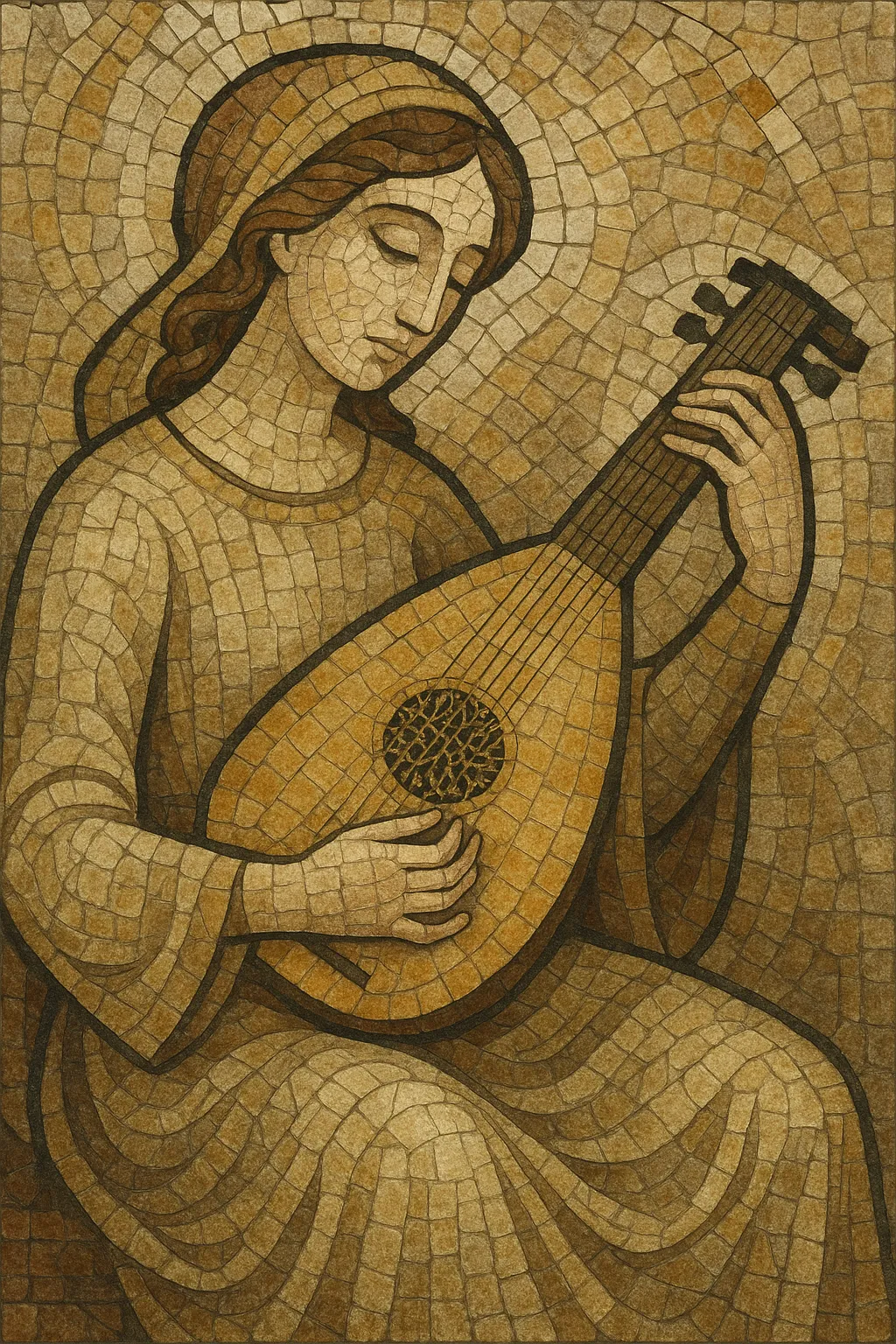

Lute song (often called an "ayre") is a late Renaissance English genre for solo voice with lute accompaniment, commonly notated so it can be performed either as a solo with lute or as a part-song by several singers with the lute doubling or elaborating the harmony.

It is characterized by clear, syllabic text-setting, elegant melodic lines tailored to poetic meters, and harmonies that sit between modal practice and emerging tonality. Many pieces are strophic, though through-composed examples occur, and performers frequently add tasteful ornamentation. The repertory ranges from courtly love lyrics to profoundly melancholic poetry—epitomized by John Dowland’s famed lachrymose style.

The English lute song emerged in the 1590s at the end of the Renaissance, absorbing techniques from Italian madrigals and French airs/chansons. English consort song traditions and the domestic music-making culture of Elizabethan England provided fertile ground for a solo-voice, lute-accompanied art that prized intelligible text and elegant melody. Early printed collections, formatted so parts could be sung by multiple voices or realized as solo with lute, reflect this flexible performance practice.

The publication of John Dowland’s First Booke of Songes or Ayres (1597) set the model for the genre’s prestige and wide circulation. Composers such as Thomas Campion (often collaborating with lutenist-publisher Philip Rosseter), Robert Jones, John Danyel, William Corkine, Thomas Ford, and others issued multiple books of ayres. The music balanced expressive word-setting with idiomatic lute writing, expanded in the early 17th century by the addition of extra bass courses to the lute, enriching accompanimental textures. Themes ranged from courtly grace to pensive and melancholic affect.

By the 1620s, English song writing gravitated toward continuo practice with theorbo or mixed continuo groups, aligning with broader Baroque trends. While the distinct print culture of the lute song waned, its aesthetics—solo voice supported by elegant plucked accompaniment and refined text-setting—fed directly into English continuo song and informed later art-song sensibilities.

Interest in early music performance restored lute song to concert life in the 20th century, aided by scholarly editions and historically informed performance. Modern lutenists and classical singers continue to record and perform this repertoire, valuing its intimate scale, poetic immediacy, and nuanced expressivity.