Your digging level

Description

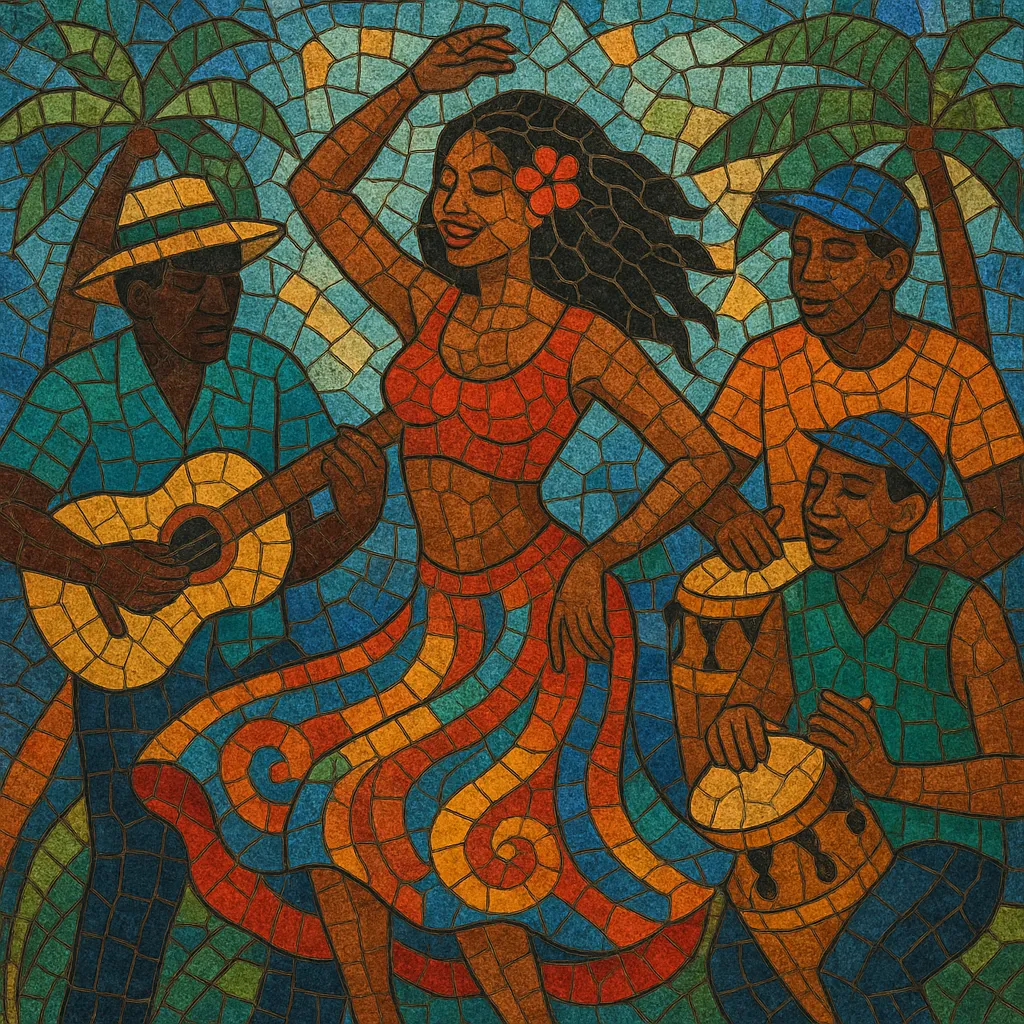

Palo de mayo is a festive Afro‑Caribbean dance‑music tradition from Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast, especially centered in Bluefields and nearby coastal towns. It is associated with Maypole festivities held throughout the month of May and blends European Maypole customs with African‑diasporic rhythms and local Creole culture.

Musically, palo de mayo is upbeat, driving, and designed for continuous dancing. Ensembles emphasize hand percussion, drum set or traditional drums, maracas, shakers, and often guitar or banjo, bass, and occasionally keyboards or horn lines. Vocals commonly use call‑and‑response and are often delivered in Nicaraguan Creole English, with playful, flirtatious double entendre and celebration of community life.

Modern palo de mayo incorporates influences from calypso, mento, soca, and reggae, while preserving the characteristic local swing and the sensual, circular dance associated with Maypole festivities.

History

Palo de mayo developed on Nicaragua’s Caribbean Coast in the 1800s, when British and other Caribbean influences brought Maypole celebrations to the Mosquito Coast. Local Creole communities fused the European Maypole custom with African‑diasporic percussion and dance aesthetics, creating a distinctly Nicaraguan Afro‑Caribbean style. Early ensembles were largely acoustic, featuring hand drums, shakers, and string instruments, supporting long, communal dances through the month of May.

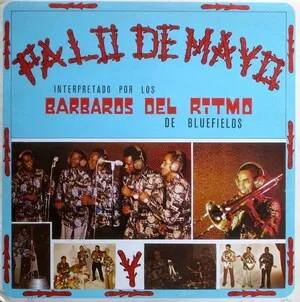

Through the mid‑1900s, palo de mayo became a hallmark of coastal festivals in Bluefields, Pearl Lagoon, Corn Island, and surrounding towns. The music absorbed regional Caribbean currents—mento and calypso from Jamaica and Trinidadian traditions—further shaping its rhythmic feel and call‑and‑response vocals. Local bands began to formalize repertoires around the festive season, preserving traditional songs while composing new ones tied to local stories, foods, and humor.

From the late 20th century onward, amplified instruments and studio production entered the style. Soca and reggae grooves influenced tempo, bass patterns, and arrangements, while lyrics continued to highlight Creole identity and May festivities. Today, palo de mayo thrives as both a living community practice—anchored by comparsas and neighborhood ensembles—and a stage style performed by professional bands that tour nationally. Annual festivals in Bluefields and other coastal towns remain the cultural heart of the genre, sustaining intergenerational transmission and attracting visitors from across Central America and the Caribbean.