Òrain Ghàidhlig refers to the traditional song repertory in the Scottish Gaelic language, rooted in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

It encompasses unaccompanied solo singing and communal song traditions, with rich ornamentation, modal melodies, and a strong relationship to dance and work rhythms. Substyles include waulking songs (òrain luaidh) for cloth-fulling, milling songs (òrain mhuilinn), mouth-music for dancing (puirt-à-beul), lullabies, love songs, laments (cumha), and narrative ballads.

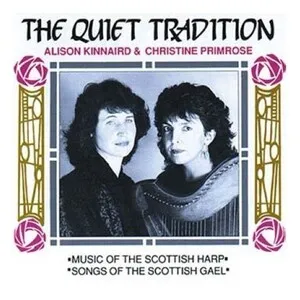

While often performed a cappella, songs may be supported by clàrsach (Scottish harp), fiddle, or pipes, yet the voice and Gaelic text remain central. Characteristic features include strophic forms with refrains, vocables (e.g., “hi o ro”), the Scotch snap in dance-derived melodies, and modal centers (frequently Dorian and Mixolydian). Themes range from landscape and community memory to clan history, courtship, and work.

Gaelic song is documented from medieval times in the Highlands and Islands, sustained primarily through oral transmission within households and communal work settings. The musical language formed alongside Gaelic poetry, where strict metrical patterns and internal rhymes influenced melodic phrasing. Over centuries, a wide taxonomy of songs emerged, including laments for clan leaders, cradle songs, and narrative ballads tied to local places and events.

In the 1700s and 1800s—amid political upheavals, the Clearances, and emigration—the repertory expanded with Jacobite songs, emigration laments, and work-songs for waulking and milling. Puirt-à-beul developed as a vocal substitute for instruments when dance music was needed, encoding reel, jig, and strathspey rhythms in syllabic vocables. Informal house ceilidhs and seasonal gatherings reinforced transmission and stylistic norms.

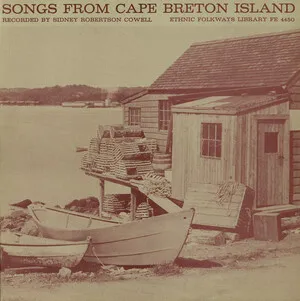

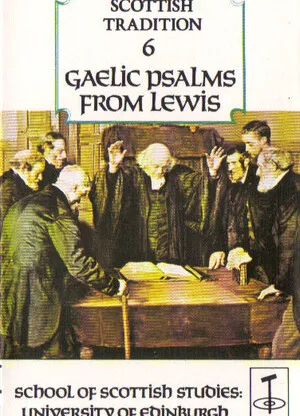

Gaelic-speaking communities in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, preserved milling song traditions into the 20th century, maintaining call-and-response formats and dance tempi. From the mid-1900s, collectors and the School of Scottish Studies made extensive field recordings, safeguarding regional styles and ornamentation. Publications and competition platforms like the Royal National Mòd helped standardize orthography and provided performance contexts for younger singers.

From the late 20th century, broadcast media, festivals, and cross-genre collaborations brought Òrain Ghàidhlig to international audiences. Artists and ensembles integrated harp, fiddle, and pipes; some fused Gaelic song with folk-rock, ambient, and electronic textures. Despite innovation, core practices—Gaelic diction, ornamented melodic lines, and strophic structures—remain central, ensuring continuity with the living tradition.