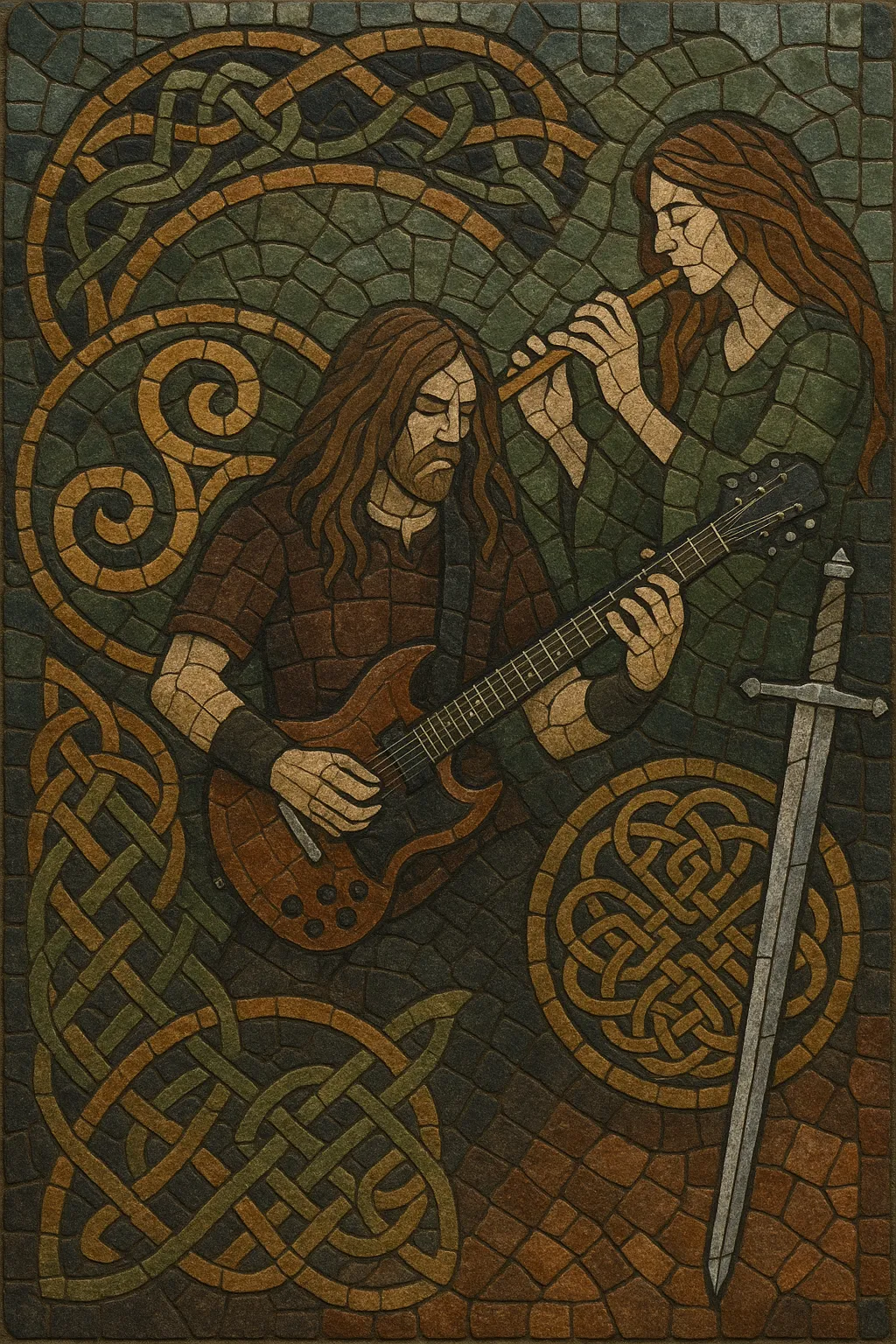

Celtic metal is a fusion of heavy metal with the traditional music of the Celtic nations, especially Ireland and Scotland. It blends distorted guitars, bass, and drums with folk instruments such as uilleann pipes, tin whistle, fiddle, bouzouki, harp, and bodhrán.

Stylistically, it often borrows rhythmic cells from jigs and reels (in 6/8 or 12/8), employs modal harmony (Dorian and Mixolydian are common), and incorporates pentatonic and drone-based melodies. The lyrical focus typically explores mythology, folklore, history, and landscapes of the Celtic world, delivered through a mix of harsh and clean vocals, sometimes in Gaelic or other Celtic languages.

The result ranges from epic, melodic arrangements to blackened, atmospheric soundscapes, maintaining a strong sense of place and tradition within a metal framework.

Celtic metal coalesced in Ireland in the early-to-mid 1990s, when bands began integrating traditional Celtic melodies and instruments into extreme and classic metal frameworks. While UK band Skyclad helped define the broader folk metal template in 1990, Irish pioneers such as Cruachan (formed 1992) and Waylander (1993) explicitly centered Irish traditional music. Primordial (formed 1987) infused black metal with Celtic themes and atmosphere, helping establish an aesthetic that foregrounded regional identity.

Cruachan’s debut "Tuatha na Gael" (1995) showcased tin whistles, bodhrán, and fiddles alongside metal riffing, effectively codifying the approach. Waylander’s "Reawakening Pride Once Lost" (1998) further emphasized 6/8 folk rhythms and pipes. Primordial’s "Imrama" (1995) and "A Journey’s End" (1998) brought a darker, epic dimension rooted in Celtic history and myth.

The 2000s saw Celtic metal expand across Europe and beyond. German band Suidakra incorporated Celtic themes into melodic death/folk metal, while Swiss group Eluveitie popularized Gaulish (Continental Celtic) concepts with hurdy-gurdy, whistles, and pipes, achieving mainstream visibility with albums like "Slania" (2008). Spanish act Mägo de Oz and Brazilian band Tuatha de Danann further demonstrated the style’s adaptability, mixing Celtic timbres with power metal and progressive elements.

Festivals and tours (e.g., Paganfest/Heidenfest) provided platforms for cross-pollination with pagan and Viking metal scenes, strengthening a pan-European folk-metal network in which Celtic metal remained a prominent branch.

In the 2010s, artists like Saor (Scotland) advanced a more atmospheric, blackened strain that fused expansive post-black textures with Highland folk motifs. The scene also saw a resurgence of historically grounded, acoustic interludes and more nuanced production techniques to better balance pipes, fiddles, and electric instrumentation.

Today, Celtic metal remains a vibrant, globally practiced idiom that emphasizes regional mythos, languages, and instruments, while engaging with contemporary metal subgenres from blackened and melodic death to symphonic and progressive styles.