Opera buffa is an Italian comic opera tradition that crystallized in the early 18th century as a lively, vernacular counterpart to opera seria.

It features everyday characters, social satire, rapid-fire patter singing (especially for the basso buffo), and bustling ensemble finales that drive the drama forward.

Musically it favors clear, galant-era melody, diatonic harmony, recitativo secco with continuo in earlier works, and increasingly sophisticated multi-voice ensembles.

Plotlines draw on commedia dell’arte archetypes and revolve around mistaken identities, class tensions, and witty intrigues, presented in the Italian language with crisp, syllabic text setting.

Opera buffa emerged in Italy—especially Naples—in the 1730s from short comic intermezzi performed between acts of serious operas. Giovanni Battista Pergolesi’s La serva padrona (1733) became a touchstone, showing how brisk recitatives, tuneful arias, and sparkling character comedy could stand on their own. Early practitioners shaped a style grounded in baroque theatrical practice but aligned with the galant aesthetic: simple textures, clear periodic phrasing, and direct word-setting.

By mid-century, composers such as Baldassare Galuppi, Niccolò Piccinni, Giovanni Paisiello, and especially Domenico Cimarosa expanded the scale and sophistication of opera buffa. The genre’s hallmark became its ensemble writing—duets, trios, and large act-ending finali that advance plot and reveal character simultaneously. Meanwhile, the tradition spread beyond Italy, influencing German-, French-, and Spanish-language comic theatres.

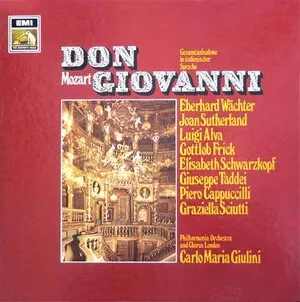

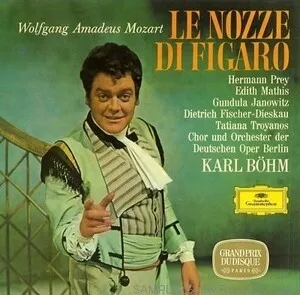

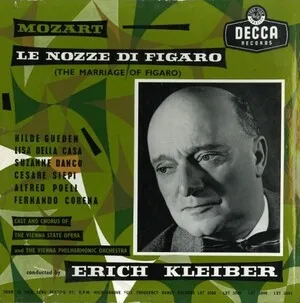

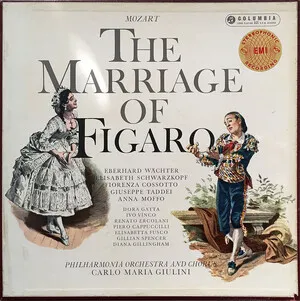

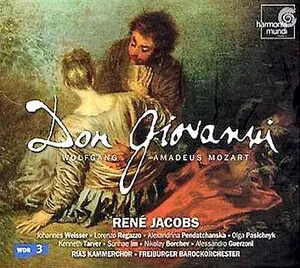

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart absorbed the Italian buffa idiom and elevated it in Viennese works like Le nozze di Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and Così fan tutte (1790). These operas integrate vivid social satire, psychological nuance, and intricate ensembles within the buffa framework, becoming canonical models for comic opera across Europe.

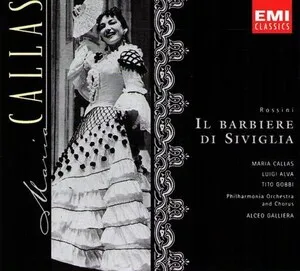

In the early 19th century, Gioachino Rossini revitalized opera buffa with virtuosic vocal fireworks and kinetic rhythmic drive (e.g., Il barbiere di Siviglia, 1816). Gaetano Donizetti continued the tradition with effervescent comedies like L’elisir d’amore (1832) and Don Pasquale (1843). While later romantic and verismo trends shifted mainstream opera toward heavier drama, opera buffa’s techniques—patter, ensemble finales, and everyday characters—profoundly influenced Singspiel, opéra comique, zarzuela, and operetta.

Opera buffa established a durable comic toolkit: the basso buffo as motor of humor, fast syllabic writing, galant/classical harmony, and ensemble-driven dramaturgy. Its DNA persists in 19th-century stage music and continues to shape comic narratives in opera houses worldwide.

Write in Italian, using crisp, syllabic text and everyday diction. Build plots from social satire, class inversion, and romantic misunderstandings. Use commedia dell’arte types—clever servants, vain nobles, blustering guardians—and give the basso buffo a central comic role with witty patter.

Organize the opera in numbers: an overture (sinfonia), alternating recitativo secco (for dialogue and pacing) and closed numbers (arias, duets, trios), and large ensemble finales that climax each act. Keep recitatives quick and functional; let ensembles advance the plot while layering character motives.

Favor galant/classical style: clear periodic phrases, diatonic harmony, and functional progressions (I–V–I, IV–V–I) with occasional secondary dominants. Aria forms can be simple binary/ternary or, in later works, cavatina–cabaletta contrasts. Give the basso buffo agile, syllabic lines for patter; write graceful cantabile for lovers and more angular motifs for schemers.

Use buoyant, dance-inflected meters (2/4, 6/8) and propulsive accompaniments (Alberti bass, light staccato strings). Maintain clarity so text is understood at high speed. In finales, build momentum by accreting voices and tightening harmonic rhythm to create comic frenzy without obscuring diction.

Score for classical orchestra: strings, pairs of oboes/clarinets/bassoons, horns, and later trumpets/timpani; use harpsichord/fortepiano continuo for secco recitatives in 18th-century style. Keep orchestration light and transparent under voices; reserve fuller tuttis for cadences and ensemble climaxes.

Craft ensembles that reveal shifting alliances and perspectives. Stagger entrances, layer contrasting motives, and use antiphony among sections. Conclude acts with extended multi-part finales that escalate through tempo and key changes, aligning musical form with comic resolution.