Your digging level

Description

Okinawan music refers to the traditional and popular musical practices of the Ryukyu (Okinawa) islands, centered on the sanshin (a three‑stringed lute) and songs in Uchinaaguchi and other Ryukyuan languages. It blends courtly traditions from the Ryukyu Kingdom with village min'yō (folk songs), ritual chant, and later 20th‑century popular styles.

Distinctive features include the Ryukyuan pentatonic scale (often heard as scale degrees 1–♭2–4–5–♭6), melismatic vocal lines, flexible rhythm, and heterophonic textures. Characteristic dances such as kachāshī (festive hand‑dance) and drum‑driven eisa are integral to the sound and performance context. In the modern era, artists have fused these roots with folk rock, pop, and worldbeat while retaining the sanshin’s timbre and island poetic imagery.

History

The Ryukyu Kingdom’s position as a maritime hub between Japan, China, and Southeast Asia fostered a courtly music culture by the 1400s–1500s. Envoy exchanges with Ming/Qing China and ties to Satsuma/Japan introduced instruments and aesthetics that shaped uta‑sanshin (song with sanshin) and refined vocal styles. Tablature known as kunkunshi standardized sanshin pedagogy.

Alongside court repertoire, village min'yō took root across Okinawa, Miyako, and Yaeyama islands. Work songs, love laments, and ritual/seasonal pieces were sung in local languages, often accompanied by sanshin, sanba (wooden clappers), and parankū (frame drum). Community dances such as kachāshī and eisa cemented music’s role in festivals and ancestor veneration.

Annexation by Japan (late 19th century) accelerated cultural exchange. Urban theaters and recordings in the early 20th century documented masters and spread regional repertoires, while contact with mainland genres influenced vocal delivery and repertoire.

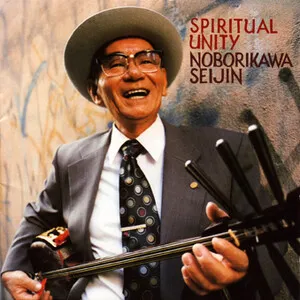

After WWII and U.S. administration, Okinawan musicians preserved heritage amid upheaval. From the 1960s onward, artists such as Rinsho Kadekaru, Seijin Noborikawa, and Sadao China revitalized min'yō. The 1970s–80s saw fusions of sanshin with rock and folk via Shoukichi Kina & Champloose, Rinken Band, and others, bringing Okinawan sounds to broader Japanese and international audiences.

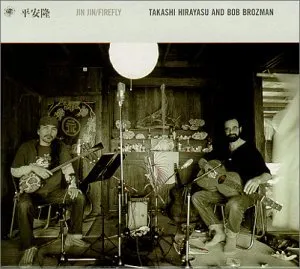

Since the 1990s, performers like Nenes, BEGIN, Rimi Natsukawa, and Takashi Hirayasu have balanced tradition with pop, worldbeat, and acoustic crossover. Archival work, school clubs, and festivals maintain classical and folk lineages, while collaborations continue to extend Okinawan music’s global footprint.