Ob-Ugric folk music refers to the traditional music of the Khanty and Mansi peoples of Western Siberia (along the Ob River basin and the Ural foothills). It is characterized by narrow-ranged, recitative-like melodies, repetitive and formulaic structures, and a strong connection to mythic narratives, hunting lifeways, and animist cosmology.

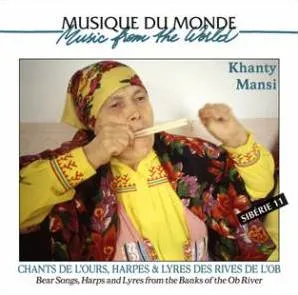

Core performance contexts include epic narrative singing, seasonal and life‑cycle rituals, and the renowned Bear Festival (Bear Games), during which long ceremonial song cycles address the sacred bear spirit. Vocal practice alternates between free, speech‑like declamation and steady dance songs, often with call‑and‑response and vocables. Accompaniment ranges from unaccompanied solo singing to simple percussion (frame drum, rattles), jaw harp drones, and occasional local lute/fiddle timbres.

The sound world is typically pentatonic or modal, with heterophonic textures when multiple voices join. Texts, delivered in Khanty or Mansi, frequently invoke place-names, clan histories, spirits, and animal protagonists.

Ob-Ugric folk music predates written history, developing as part of the Khanty and Mansi’s Uralic-speaking cultures in the forests and river systems of Western Siberia. The 19th century (1800s) brought the first sustained ethnographic descriptions and later audio documentation by Russian and European scholars, which is why this era is often used as the conventional point of origin in music-historical timelines.

At the heart of the tradition is ritual performance, especially the Bear Festival (often translated as Bear Games), where extended song cycles address the bear’s spirit, recount hunt episodes, and maintain cosmological balance. Beyond ritual, epic narrative singing, laments, children’s songs, and round dances functioned as repositories of clan memory and practical knowledge. Oral transmission—through families, clan leaders, and designated song specialists—sustained a large repertory with regional variants (e.g., Kazym, Sosva, Lozva traditions).

Soviet-era settlement policies, language shift, and restrictions on ritual life disrupted many traditional performance contexts. Yet, collectors, linguists, and ethnomusicologists recorded valuable audio archives, and local cultural houses fostered staged folk ensembles. From the late 20th century onward, there has been renewed cultural activism in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug: festivals, museums, and education programs support language preservation and the respectful revival of ritual songs in appropriate community settings.

Today, Ob-Ugric music appears both in community rituals and on stage, where it is sometimes adapted for ensemble presentation. It also circulates through archives, curated releases, and collaborations in world-fusion contexts, increasing international awareness while raising ongoing discussions about cultural protocols and ethical performance.