Ngâm thơ is the Vietnamese art of chanting poetry, a semi-sung declamation that traces the tones, rhythm, and imagery of classical verse. Rather than following a fixed tempo or strophic melody, the reciter shapes phrases freely, allowing the language’s six tones and poetic prosody to guide melodic contour and pacing.

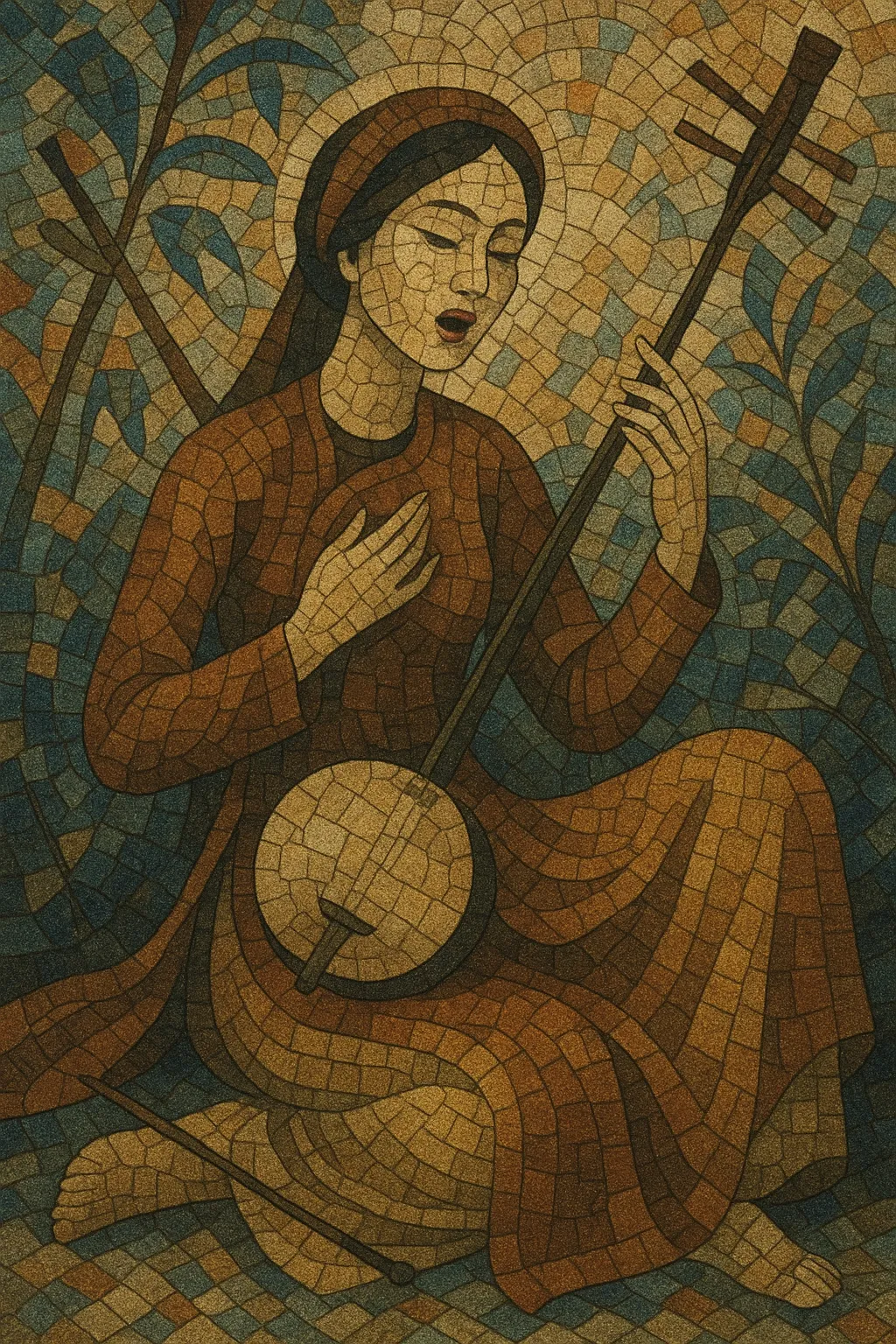

Performances range from intimate, unaccompanied recitation to chamber settings with đàn bầu (monochord), đàn tranh (zither), đàn nguyệt (moon lute), sáo trúc (bamboo flute), or đàn nhị (two-string fiddle). The melodic language often draws on traditional modal aesthetics (hơi Bắc, hơi Nam, hơi Oán), with expressive slides, microtonal inflections, and ornamental turns that mirror the semantic and emotional weight of each line.

Ngâm thơ is heard in literary salons, radio broadcasts, school settings, cultural festivals, and domestic rituals. It embodies the meeting point of poetry and music in Vietnam, making verse physically audible through tone, timbre, and gesture.

Ngâm thơ emerged from Vietnam’s literati culture, where learned poetry—often in forms such as lục bát (6–8), song thất lục bát (7–7–6–8), and Đường luật (regulated verse)—was recited aloud to savor tone, rhythm, and metaphor. By the 1800s, recitation practices had taken on distinct melodic contours, influenced by courtly and chamber performance aesthetics and by the broader habit of musicalized speech in ritual and theatrical contexts.

The style shares a family resemblance with ca trù (chamber art with refined vocalization and flexible rhythm), theatrical declamation in hát tuồng (Vietnamese classical opera), folk narrative delivery in xẩm (street balladry), and responsive lyricism in quan họ (antiphonal love songs). These neighboring traditions shaped the expressive palette of ngâm thơ—its attention to tonal nuance, free rhythm, and micro-ornamentation.

With the rise of radio in the mid-20th century, ngâm thơ reached mass audiences through dedicated poetry programs. Teachers, poets, and announcers helped codify a broadcast style that emphasized clear diction, controlled vibrato, and tasteful instrumental backing. Recordings of canonical works (e.g., excerpts from Nguyễn Du’s Truyện Kiều) became reference points for performance practice.

Today, ngâm thơ appears in cultural festivals, academic settings, and multimedia adaptations. Ca trù clubs and theater companies continue to feature poetry chanting in curated programs, while modern performers adapt the style for staged readings, film, and cross-genre collaborations. The tradition remains a living interface between Vietnam’s classical poetry and its musical imagination.

Select a Vietnamese poem (lục bát, song thất lục bát, or Đường luật). Mark tonal patterns and caesuras, and note rhetorical peaks (metaphors, turns, or enjambments). The poem’s tone contours and rhyme scheme will drive phrasing.

Decide on a modal flavor (hơi Bắc for brightness, hơi Nam or hơi Oán for plaintive color). Outline flexible melodic cells that rise and fall with the language’s tones, using microtonal slides, light portamento, and ornamental turns to mirror meaning and intensify emotion.

Maintain a free, speech-derived rhythm. Let line endings breathe; elongate key syllables; and pace climaxes according to semantic emphasis, not the barline. Use rubato and silence as expressive tools.

For accompaniment, favor đàn bầu, đàn tranh, đàn nguyệt, sáo trúc, or đàn nhị in sparse textures. Sustained drones, delicate arpeggios, and short cadential motifs support the voice without imposing a strict beat. Call-and-response gestures between instrument and voice can highlight imagery.

Prioritize clear articulation of tones and vowels. Employ gentle vibrato, controlled dynamics, and careful breath placement. Align melodic motion with tonal inflection: rising tones may lift the pitch contour; falling or heavy tones can settle into a cadence or ornamental turn.

Shape the overall arc by grouping stanzas into sections that rise to thematic peaks. End sections with recognizable cadential gestures (brief instrumental tags or formulaic closing tones) to signal closure while preserving the poem’s integrity.