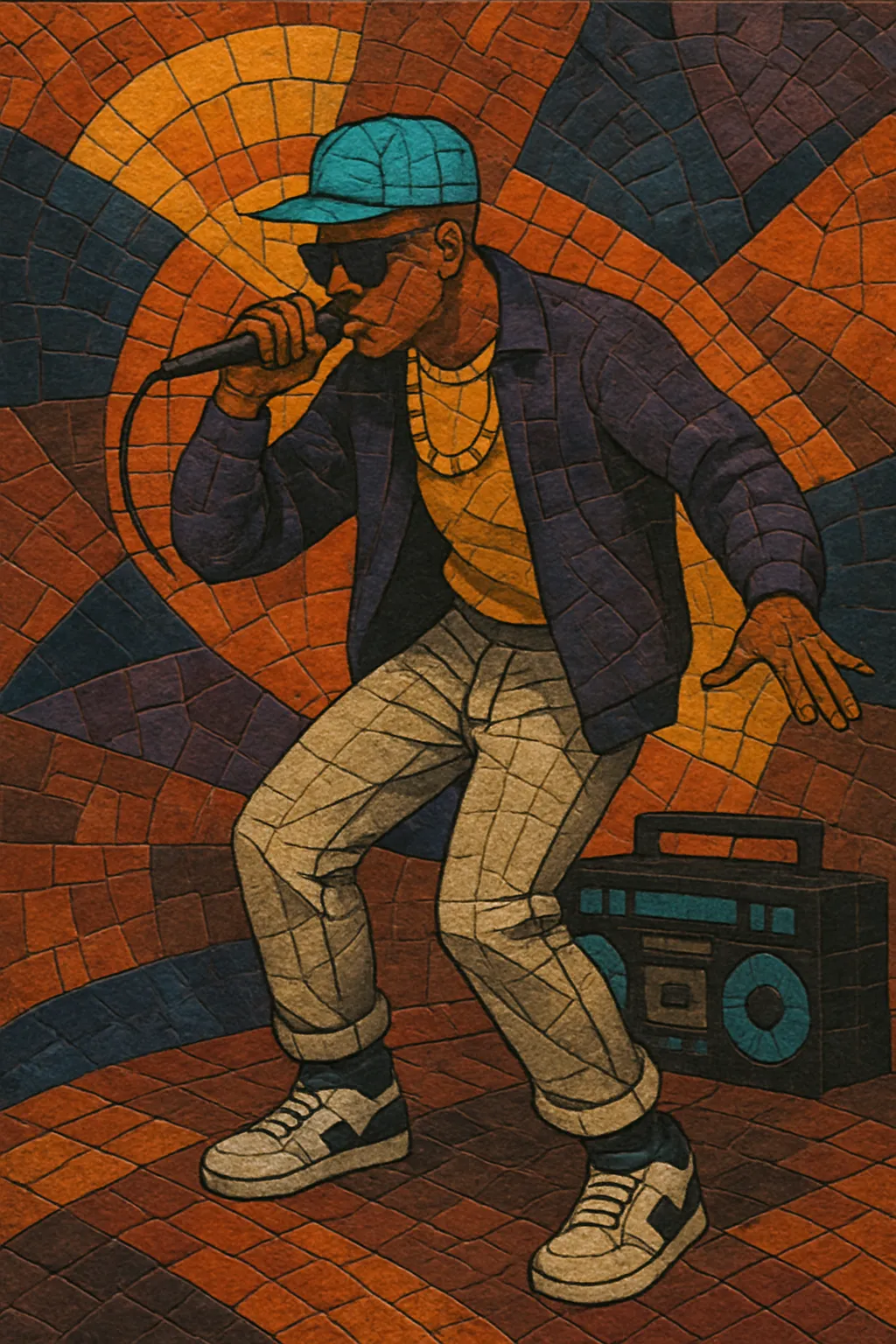

New jack swing is a late‑1980s fusion of contemporary R&B vocal harmony and melodies with hip‑hop’s drum programming, sampling aesthetics, and street attitude.

It is defined by swung, hard‑hitting drum‑machine grooves (often with gated snares), bright synth stabs and bass, and a slick, dance‑oriented production style. Producers and vocal groups combined rap verses or talk‑style ad‑libs with smooth, hook‑forward choruses, making the sound equally suited for radio and choreography‑heavy performances.

The style dominated U.S. pop and R&B charts from the late 1980s into the early 1990s, influencing mainstream pop as well as the first waves of K‑pop and shaping the trajectory of 1990s contemporary R&B.

New jack swing emerged in the mid‑1980s in the United States when producers and songwriters—most iconically Teddy Riley—merged contemporary R&B singing with hip‑hop’s drum programming and sample‑based textures. The term “new jack swing” was popularized in late‑1980s music journalism, capturing a fresh, youthful (“new jack”) take on R&B. Foundational early signposts include Janet Jackson’s Control (1986) and the Jam & Lewis production aesthetic, which helped pave the lane for a harder, hip‑hop‑leaning R&B sound.

Keith Sweat’s Make It Last Forever (1987), Guy’s debut (1988), Bobby Brown’s Don’t Be Cruel (1988), and Bell Biv DeVoe’s Poison (1990) brought the sound to the mainstream. The style’s calling cards were swung 16th‑note drum‑machine grooves, bright digital synths (DX7‑style EPs, brass stabs), punchy gated snares, and a synthesis of sung hooks with occasional rap sections. The era saw crossover pop success and a visual identity centered on sharp choreography and urban fashion.

By the mid‑1990s, hip hop soul and neo‑soul shifted R&B toward grittier sampling or organic instrumentation, and pure new jack swing receded from the charts. Its DNA, however, remained crucial to 1990s contemporary R&B, teen pop vocal groups, and the first generation of K‑pop producers and idols who adopted its polished, dance‑centric template. Periodic revivals and retro‑influenced tracks continue to reference its signature swingbeat drums, glossy synths, and hook‑driven writing.

• Aim for 100–112 BPM with a pronounced swing (swung 16ths). The groove should feel bouncy and dance‑driven.

• Program the backbeat on 2 and 4 with tight, punchy snares. Use subtle ghost notes and off‑beat hi‑hats for forward motion.

• Use classic drum machines/samplers (Linn, SP‑1200, TR‑808/909) or their modern equivalents. Layer a gated, bright snare with a short plate reverb.

• Add syncopated percussion (congas, claps, tom fills, cowbells) and occasional “orchestra hit” stabs for accents.

• Write R&B‑centric progressions with 7ths/9ths and suspended chords. Common keys favor vocal brightness (E♭, F, G♭ major).

• Compose strong, repetitive hooks with call‑and‑response between lead and backing vocals.

• Use a percussive, synthesized bass (FM or analog) locking tightly with the kick. Basslines are often stepwise and syncopated.

• Layer DX‑style electric pianos, bright brass stabs, and glassy pads. Short, rhythmic chord stabs reinforce the groove.

• Combine smooth lead vocals with stacked harmonies and ad‑libs; optionally include a brief rap bridge or breakdown.

• Lyrical themes center on romance, swagger, nightlife, and feel‑good confidence.

• Structure: intro hook → verse → pre‑chorus → chorus → verse → chorus → bridge/rap → final chorus with ad‑libs.

• Use swing quantize (not straight) on drums and rhythm parts; keep mixes glossy with controlled reverb, slap delays on vocals, and tight bus compression to accentuate punch.

• Choreography matters: arrange breaks for dance routines. Keep transitions crisp and emphasize audience‑grabbing hooks.