Your digging level

Description

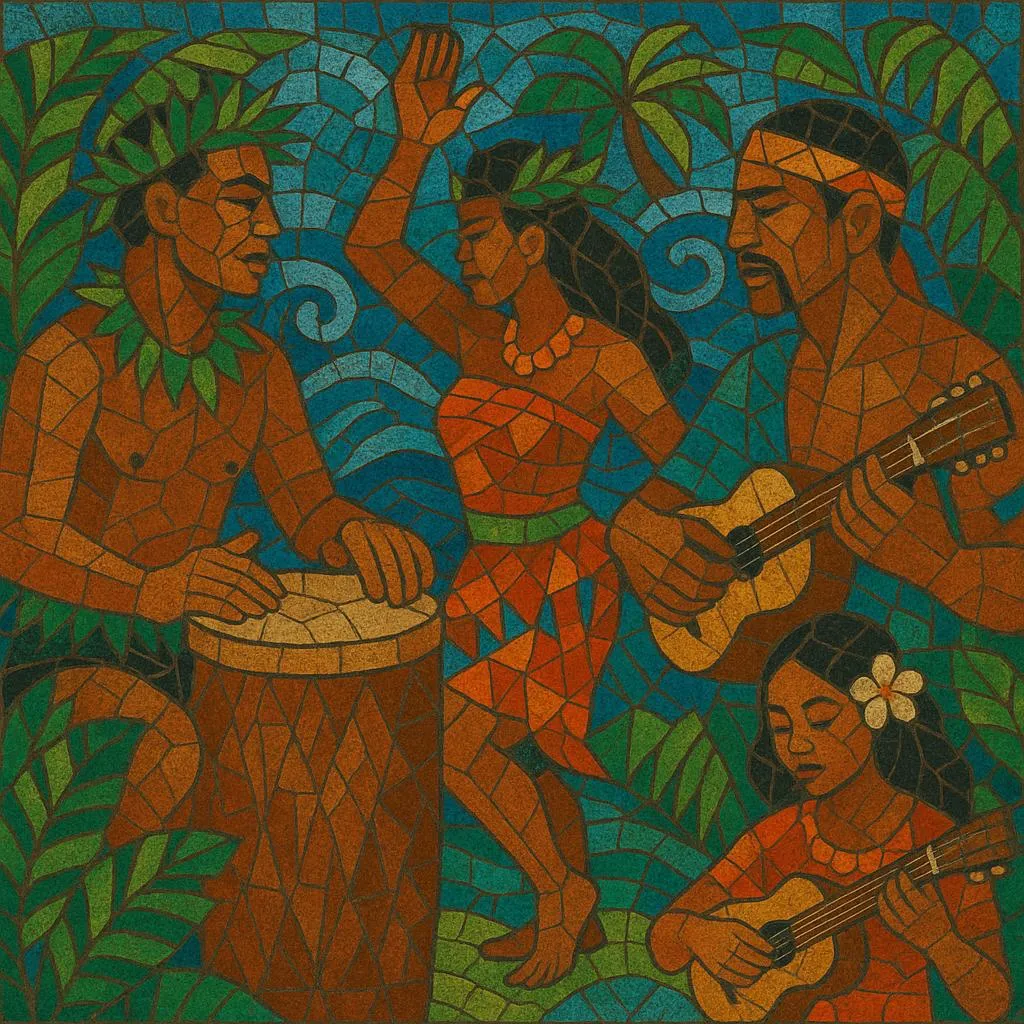

Music of the Pacific Islands refers to the diverse traditional and contemporary musics found across Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. It encompasses vocal polyphony, chant, communal dance-music, and rich percussion traditions, as well as later hybrids with hymnody, guitars/ukuleles, and reggae-derived styles.

While each island group and people has distinct practices (e.g., Tahitian to’ere drumming, Hawaiian mele and hula, Fijian meke, Kiribati antiphonal song, PNG garamut ensembles, and ʻukulele/guitar-led string bands), common threads include communal performance, call-and-response textures, close ties to dance and ceremony, and strong relationships between music, genealogy, place, and language.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, missionary hymnody, military bands, and broadcast media introduced new harmonies and instruments that blended with indigenous aesthetics. Today, traditional forms coexist with and inform modern genres like Jawaiian, Pacific reggae, vude, and showband styles.

History

The Pacific Islands’ musical cultures trace to ancient Austronesian migrations and deep-time settlement patterns across Polynesia, Micronesia, and Melanesia. Music was (and remains) embedded in oral tradition, dance, and ritual: from Hawaiian mele and hula to Tahitian himene and to’ere drumming; from Kiap string-bands and garamut slit-drum ensembles in Papua New Guinea to antiphonal and polyphonic singing in Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Kiribati, and the Solomon Islands.

European contact and Christian missionization introduced hymnody, choral part-singing, and Western instruments (guitars, ukuleles, brass/woodwinds). Islanders adapted these influences, developing distinctive four-part choral styles, ukulele and guitar accompaniments, and band formats that sat alongside (rather than replaced) indigenous percussion and chant.

The spread of radio, records, and later cassettes supported regional circulation of styles: Hawaiian ensembles popularized the ʻukulele and steel guitar; string-band idioms thrived in Melanesia; and choral forms expanded beyond liturgical contexts. Local dance-music (e.g., Tahitian ‘ori, Fijian meke) continued to anchor identity in festivals and ceremonies.

From the late 20th century onward, Jawaiian (Hawaiian-local reggae) and Pacific reggae linked island rhythm and harmony with roots reggae backbeats. In Fiji, vude fused meke aesthetics with pop; showbands and cultural troupes professionalized staged presentations; and diasporic communities (e.g., in Aotearoa/New Zealand, the U.S., and Australia) cultivated crossovers with pop, R&B, and hip hop. Across the region, heritage transmission, school programs, and festivals (e.g., Heiva i Tahiti, the Festival of Pacific Arts) sustain traditional forms in dialogue with contemporary creativity.