Mesoamerican music refers to the pre‑Columbian musical traditions of the civilizations that flourished in present‑day Mexico and parts of Central America (e.g., Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Mexica/Aztec). Emerging as early as the Preclassic period (circa 1500 BCE), it developed a rich ceremonial sound world built around aerophones (clay ocarinas, whistles, flutes, conch shell trumpets), membranophones (huehuetl single‑headed drums), idiophones (rattles, slit‑drum teponaztli), and voice.

Rather than harmony in the Western sense, the music emphasizes timbre, cyclical rhythms, antiphonal chant, and heterophonic textures that accompany dance, poetry, ritual, warfare, and calendrical observances. Musical practice was embedded in civic‑religious life—performed in temples, courts, and plazas—and encoded in pictorial codices and sculpture that depict instruments, ensembles, and performance contexts.

Archaeological and iconographic evidence places the origins of Mesoamerican music in the Preclassic period (ca. 1500 BCE). Clay ocarinas and whistles, bone and cane flutes, conch (atecocolli) trumpets, and slit drums (teponaztli) appear in early sites and later in codices and reliefs. Music was integral to ritual life, calendrical ceremonies, and the ballgame, with ensembles accompanying dance, poetry, and processions.

By the Classic and Postclassic eras, urban centers (e.g., Teotihuacan, Tikal, Tenochtitlan) institutionalized musical training in houses of song (cuicacalli/calmecac). Aztec sources describe vocal genres (cuicatl) and detailed the use of huehuetl and teponaztli in public festivals, war rites, and temple ceremonies. Maya courts cultivated refined flute/whistle repertoires and ritual chant, documented in murals, ceramics, and glyphic texts.

The sound palette favored breathy aerophones and resonant wooden/cane drums. Teponaztli provided two defined pitches, often used in ostinati. Vocal delivery ranged from declamatory chant to melismatic invocation, frequently in call‑and‑response. Pitch systems were diverse and context‑specific (anhemitonic/pentatonic tendencies are attested in reconstructions), with heterophony and rhythmic cycles prevailing over vertical harmony.

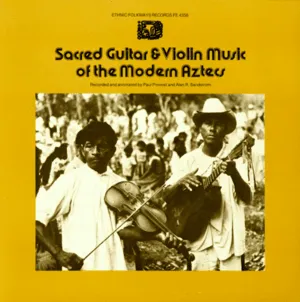

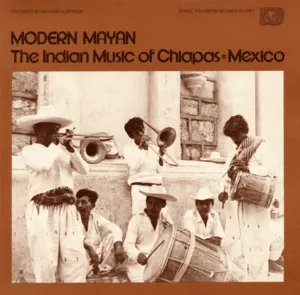

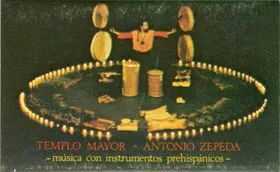

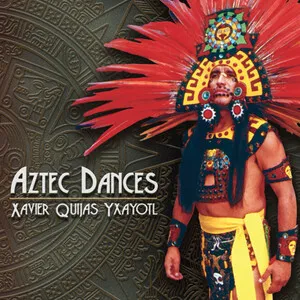

After the 16th‑century conquest, many ceremonial contexts were suppressed or syncretized. Nevertheless, core instrument types (drums, flutes, rattles, conch), dance‑music complexes, and ritual specialists persisted in Indigenous communities (Nahua, Maya, Mixe‑Zoque, Totonac, etc.). Modern revivalists and community ensembles have reconstructed repertoires from archaeological finds, codices, and ethnography, while contemporary Mexican and Central American artists incorporate pre‑Hispanic instrumentation into new works.

From the late 20th century onward, Mexican artists and research groups popularized pre‑Hispanic instrument building and performance practice, presenting concert reconstructions and intercultural fusions. These efforts inform museum programs, community festivals, and recordings, keeping Mesoamerican sound worlds active in the present.