Mbenga–Mbuti music refers to the richly polyphonic vocal and ritual music of forest-dwelling peoples of Central Africa, especially the Mbuti of the Ituri (in today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo) and the Mbenga groups such as the Aka/Baka (in the Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, and Gabon).

Characterized by dense vocal counterpoint, yodeling timbres, interlocking ostinatos (hocket), and flexible polyrhythms, the style is primarily vocal and communal. Songs function in daily life (net-hunting, lullabies), rites of passage (e.g., Elima), and forest rituals (e.g., Molimo), with music conceived as a living dialogue with the forest itself. Instruments are sparse and often makeshift (handclaps, sticks, rattles, water drumming, simple whistles such as hindewhu, and ceremonial trumpets like the molimo), with the voice acting as the central instrument.

The sound world is bright, buoyant, and resonant, often floating between earthy groove and otherworldly shimmer. While its origins are prehistoric, the genre became known internationally through 20th‑century ethnographic recordings that revealed its sophisticated polyphony and polyrhythm to a global audience.

The musical practices associated with Mbenga–Mbuti communities are among the oldest living musical traditions on Earth, evolving alongside forest lifeways over countless generations. Music accompanies subsistence activities (notably collective net-hunting), social bonding, healing, and lifecycle ceremonies. Rituals such as the Molimo (with its long trumpet) are sonic dialogues with the forest, conceived as a sentient presence that must be awakened, praised, or appeased.

The core aesthetic is communal polyphony. Singers weave interlocking ostinatos that cycle independently, creating shimmering textures through hocket (sharing a melody among several voices), yodeling (rapid alternation of chest/head registers), and polyrhythm. Harmony is emergent rather than planned—there is no fixed chord progression—yet the result is tightly knit, buoyant, and danceable. The forest’s acoustics and daily routines shape tempo, timbre, and form.

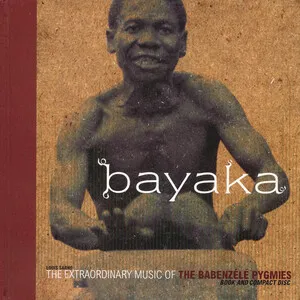

Although prehistoric in origin, Mbenga–Mbuti music reached global ears in the 20th century via fieldwork and recordings by ethnographers and labels such as UNESCO, Ocora, and Smithsonian Folkways. Researchers including Simha Arom and Colin Turnbull documented the music’s structure and social context, demonstrating its sophisticated rhythmic layering and multipart vocal organization.

These recordings profoundly influenced composers, improvisers, and producers. Minimalist, experimental, and ambient artists cited the interlocking cycles, non-harmonic counterpoint, and additive processes as inspirations. Popular musicians and electronic producers sampled elements such as hindewhu (voice–whistle alternation) and water drumming, sometimes controversially, seeding ideas into worldbeat and various strands of global fusion.

Today, community ensembles continue to perform in ceremonial and everyday settings, and some groups present concerts or albums to support cultural preservation. Despite external pressures on forests and lifeways, the music remains a living, adaptive practice anchored in communal participation and reciprocity with the environment.