Central African music is an umbrella term for the traditional and popular styles that emerged in and around the Congo Basin, including today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and parts of Chad and Angola.

It blends deep-rooted forest and Bantu musical practices—polyphonic vocal traditions, call-and-response singing, interlocking rhythms, slit- and frame-drum ensembles, thumb pianos (likembe/sanza), and xylophones—with urban dance-band instrumentation and Latin/Caribbean influences brought by early records from Cuba. In the mid‑20th century these elements crystallized in highly influential guitar-led dance musics (notably Congolese rumba and, later, soukous/ndombolo), alongside Cameroonian scenes such as makossa and bikutsi.

Signature traits include buoyant, cyclical grooves; bright, interlocking guitar parts (the sebene); syncopated bass ostinatos; bell and shaker time-lines; and exuberant call-and-response vocals in languages such as Lingala, French, Sango, Duala, and others. The result ranges from tender, romantic rumba ballads to fast, ecstatic dance pieces that dominate social life and regional club culture.

Central African music descends from millennia of forest and Bantu cultural practices. Hunter–gatherer communities (e.g., Aka/BaAka) developed intricate, participatory polyphony with hocketing and yodeling, while Bantu-speaking groups cultivated slit-drum (lokole/ngoma) and xylophone ensembles, call-and-response singing, and cyclical dance rhythms. These practices formed the aesthetic foundation for later urban popular styles.

By the 1930s–40s, cities like Léopoldville (Kinshasa) and Brazzaville hosted dance bands that absorbed imported shellac records from Cuba. Musicians recognized affinities between African rhythmic cycles and Cuban son/rumba, reinterpreting them on guitars, bass, and horns. Pioneers like Joseph "Grand Kallé" Kabasele helped codify a local rumba sung in Lingala, setting the stage for a modern Central African sound.

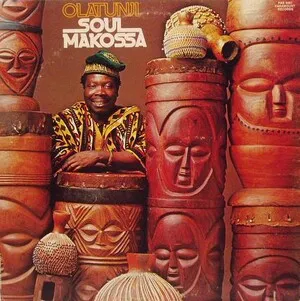

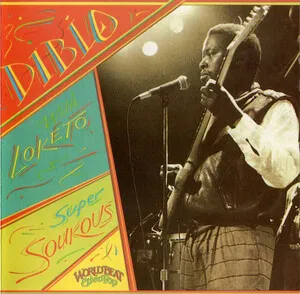

The 1950s–60s saw Congolese rumba flourish with luminous guitar interplay (rhythm/mi-solo/lead) and long dance codas (sebenes). Icons such as Franco, Dr. Nico, Tabu Ley, and OK Jazz/TP OK Jazz defined the repertoire. In Cameroon, makossa and bikutsi matured; Manu Dibango’s global hit "Soul Makossa" (1972) showcased the region’s funk-tinged horn writing and infectious bass figures.

Faster tempos and extended sebenes drove soukous across Africa and the diaspora, leading to spectacular stage shows and pan-African popularity. Ndombolo and kwassa kwassa dance crazes emerged from Kinshasa and Paris/Brussels expatriate scenes. Papa Wemba, Koffi Olomidé, Zaiko Langa Langa, and Pepe Kallé became household names. Meanwhile, the forest polyphonies of Aka/BaAka communities gained global recognition, including heritage accolades for their vocal art.

Contemporary stars like Fally Ipupa modernize rumba/ndombolo with sleek production while maintaining the genre’s vocal warmth and guitar clarity. Cameroonian makossa/bikutsi intersect with Afropop and club electronics. Despite political and economic challenges, Central African music remains a cornerstone of African popular culture and a key influence on East, West, and Southern African dance music scenes.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)