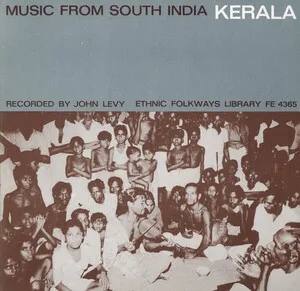

Malayali folk music is the diverse body of traditional song and musical practices of the Malayalam‑speaking communities of Kerala, India. It spans ritual, occupational, festive, and narrative forms, and is closely tied to everyday life, seasonal cycles, and community identities.

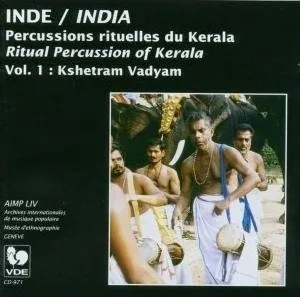

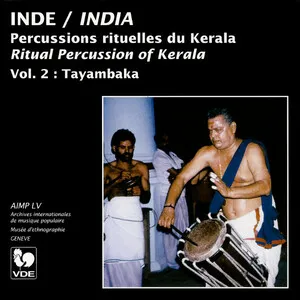

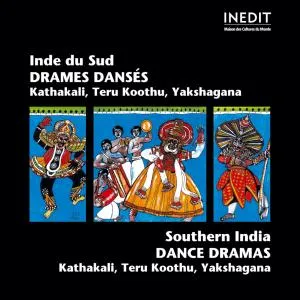

Signature styles include Vanchippattu (boatmen’s rowing songs), Thiruvathirappattu (women’s circle-dance songs), Onappattu (harvest/Onam songs), Mappila Pattu and Oppana (songs of Kerala’s Muslim community reflecting Arabic and Persian influences), Pulluvan Pattu (snake‑worship ritual songs), Theyyam thottam pattu (invocatory songs of the Theyyam ritual), and Sopanam (temple-ritual singing). The music favors modal melodies, cyclic rhythms (tala), antiphony and call‑and‑response, and the distinctive timbres of Kerala’s percussion and wind ensembles.

While many melodies are non‑classical and oral, several strands interact with Carnatic (South Indian) ragas and rhythmic frameworks, as well as Arabic/maqam aesthetics in Mappila traditions. The result is a living, community‑based music that balances devotional intensity, festive energy, and storytelling.

Kerala’s folk repertories crystallized between the 1600s and 1800s out of older oral traditions tied to work, worship, and celebration. Boatmen’s Vanchippattu arose along Kerala’s backwaters; women’s Thiruvathirappattu accompanied winter solstice and Onam festivities; Pulluvan Pattu emerged from serpent‑worship rites; and Theyyam songs preserved myths and hero narratives of North Malabar. Muslim Mappila communities in Malabar developed Mappila Pattu and Oppana, blending Malayalam poetics with Arabic/Persian vocabulary and melodic turns.

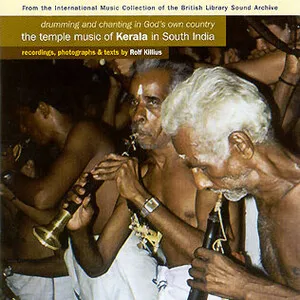

Folk strands interfaced with temple and court cultures. Sopanam, a temple‑ritual singing tradition, shares modal/rhythmic kinship with Carnatic music while keeping a distinct, austere delivery accompanied by idakka, chengila, and ilathalam. Poets like Ramapurathu Warrier (Kuchelavritham Vanchippattu) and Kunchan Nambiar (Ottan Thullal) popularized narrative and satirical song forms with strong folk footing.

Across the 19th century, print culture and community poets such as Mahakavi Moyinkutty Vaidyar codified Mappila ballads, while Christian communities nurtured Margamkali and Parichamuttukali song‑dance traditions. Folk ensembles remained central at festivals (Onam, temple utsavams) and in occupational contexts (paddy fields, boat races).

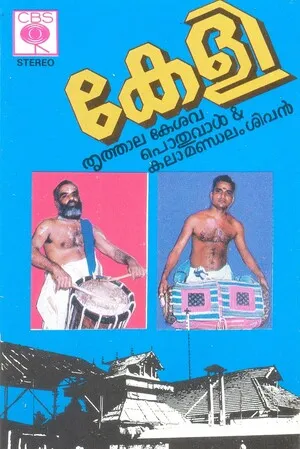

From the mid‑20th century, radio and cinema carried naadan pattu (folk‑flavored songs) statewide. Vallamkali (boat race) anthems, Oppana numbers, and Onappattu entered Malayalam film and popular recordings, while exponents of Sopanam, melam (percussion orchestras), and Theyyam kept ritual lineages vibrant.

Today, cultural festivals, folk research centers, and digital archives document and teach these traditions. Artists blend Malayali folk idioms with indie, world‑fusion, and even metal (e.g., Theyyam‑themed fusions), ensuring continuity while inviting new audiences.

Aim for modal (raga‑like) melodies with limited harmonic movement, delivered in unison or light heterophony. Favor call‑and‑response and antiphony between lead and chorus, reflecting communal performance.