South Asian folk music is an umbrella term for the village- and community-rooted song and dance traditions of the Indian subcontinent, including present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka.

It is characterized by orally transmitted melodies, strophic song forms, participatory call-and-response, and region-specific rhythms, instruments, and languages. While distinct from the codified classical systems, it often borrows ragas, drones, and tala-like cycles, translating them into everyday, ceremonial, and seasonal contexts such as harvests, weddings, religious festivals, and storytelling.

Typical timbres include the twang of the ektara and dotara, the buzzing reeds of the shehnai and algoza, the resonant dhol and dholak, and the expressive voice supported by harmonium and drone. Themes range from spiritual devotion (Bhakti and Sufi poetry) to love, labor, migration, satire, and nature, with performances designed for dancing, communal bonding, and ritual.

South Asian folk music predates written history, evolving through oral traditions in village societies. From the medieval period onward, devotional movements such as Bhakti and Sufism deepened the lyrical and spiritual content of local song, bringing saint-poets and mystic minstrels (e.g., Bauls, fakirs) into village squares and pilgrimage routes. While distinct from courtly and classical practices, folk idioms absorbed raga-like melodic contours, drones, and cyclical rhythms.

Across the subcontinent, diverse regional idioms flourished: Punjabi tappas and dance songs with dhol-driven grooves; Bengali Baul and Bhatiyali boat songs; Assamese Bihu tied to seasonal cycles; Rajasthani Manganiyar and Langa repertoires with sarangi, kamaicha, and kartal; Marathi lavani with its theatrical energy; Kashmiri wanwun wedding songs; Sindhi and Saraiki kafi; Tamil village songs; and Nepali lok geet. Each maintained local languages, instruments, and performance practices while sharing broader South Asian sensibilities.

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw missionaries, folklorists, and gramophone companies document and commercialize folk repertoires. Post-independence nation-building (mid‑20th century) promoted folk arts on radio (AIR), state academies, and festivals, while cinema adapted folk melodies into film songs. Urbanization and migration created new audiences, and folk practitioners increasingly engaged with staged performance and recording studios.

From the late 20th century, diaspora communities and popular media amplified South Asian folk globally. Punjabi folk rhythms catalyzed bhangra and later pop-bhangra; Sufi-oriented vernacular styles informed qawwali’s worldwide prominence and later sufi rock; Indo-Caribbean communities transformed Bhojpuri-rooted folk into chutney and chutney soca. Contemporary artists and producers now blend regional folk textures with pop, electronic, and indie frameworks, sustaining tradition while innovating.

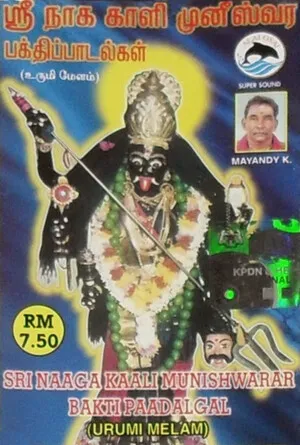

%20%5BSri%20Naaga%20Kaali%20Munishwarar%20bakti%20paadalgal%20(Urumi%20melam)%5D%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)