Malay classical music (Muzik Klasik Melayu) is the refined, courtly and urban song-and-dance tradition of the Malay world that crystallized in the 19th and early 20th centuries across the Malay Peninsula and the Straits Settlements. It blends indigenous court repertories (nobat and istana traditions) with Arab-Persian modal practice, North Indian ghazal poetics, Portuguese-Eurasian serenade strains (dondang sayang), and later European salon instrumentation.

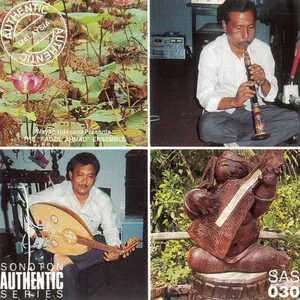

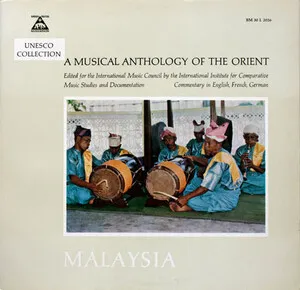

Core song-types include asli (slow, melismatic art song), inang (graceful court dance), joget (lively social dance), zapin (Arabic-rooted devotional dance adapted for entertainment), dondang sayang (improvised love-verse exchange), and ghazal Johor (Malay take on the ghazal). Typical ensembles center on voice with biola (violin), gambus/oud, rebab, accordion or harmonium, serunai (shawm) in ceremonial contexts, and frame and barrel drums (gendang, rebana/kompang). Melodic lines are heavily ornamented, lyrics are built from pantun and syair poetry, and rhythms follow characteristic cycles (e.g., zapin in 6/8; joget in brisk duple).

The foundations lie in Malay court culture linked to the Malacca Sultanate and its successor states. Royal nobat ensembles (with nafiri/serunai and drums) provided ceremonial music, while courtly poetry (pantun, syair) shaped an aristocratic vocal aesthetic. Maritime trade brought sustained contact with Arab, Persian, Indian, and later Portuguese worlds, planting seeds for modal practice and verse forms that would later be absorbed into entertainment genres.

In the 1800s, urban centers such as Melaka, Penang, and Singapore became melting pots. Portuguese-Eurasian serenade traditions influenced the birth of dondang sayang; Arab-Hadhrami networks and Indian musicians helped localize zapin and ghazal into Malay social settings; and violin, accordion/harmonium, and gambus entered mixed ensembles. This period consolidated the core song-dance types—asli, inang, joget, zapin—and refined a distinctly Malay classical sensibility.

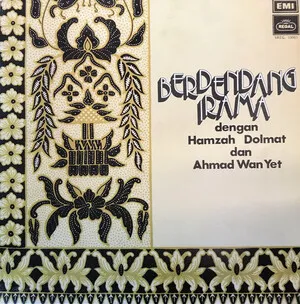

Recording, radio, and film (notably the Malay studio era of the 1940s–1960s) propelled Malay classical song into the public sphere. Orkes Melayu and broadcasting institutions (later RTM) standardized repertoires and ensemble formats, while star vocalists popularized the style for mass audiences without severing ties to poetic pantun craft and ornamental singing.

While pop and rock diversified Malay music, classical forms persisted in cultural bodies, arts academies, and state ensembles. Ghazal Johor and dondang sayang traditions continued on stage and airwaves, with heritage programs supporting transmission. Dondang Sayang of Melaka was recognized on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, underscoring the genre’s living classical status. Today, artists and orchestras bridge classical idioms with modern arrangements, keeping the modal language, poetic structures, and dance rhythms alive.