Magyar nóta (often simply “nóta”) is a 19th‑century Hungarian urban art‑song tradition that blends folk‑derived melody with salon polish. Although commonly performed by Roma (Gypsy) string bands, the repertoire was largely composed by Hungarian songwriters and circulated through cafés, restaurants, and civic festivities.

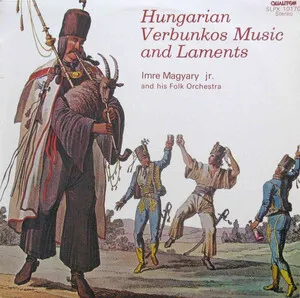

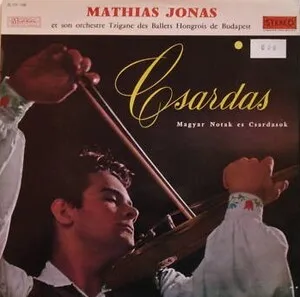

Musically, nóta alternates between parlando‑rubato declamation and stricter dance‑like sections, drawing on verbunkos and csárdás idioms. Signature traits include ornamented violin lines (prímás), expressive portamento, the use of the "Hungarian minor" (so‑called Gypsy minor) color with augmented seconds, and accompaniment by cimbalom, kontra (chord viola), clarinet or tárogató, and double bass. Lyrically, it centers on love, longing, homesickness, wine, and national sentiment, delivered with direct, emotive phrasing.

Historically, it became the emblematic café music of the Austro‑Hungarian era, later becoming both a nostalgic symbol and a contested category often misidentified as generic “Gypsy music.”

Magyar nóta crystallized in the urban centers of the Kingdom of Hungary during the mid‑1800s. It absorbed melodic turns and rhythmic profiles from verbunkos recruiting music and the csárdás dance, while adopting salon conventions and strophic song forms. Roma prímások and bands popularized nóta in cafés and social clubs, giving the style its widely recognized sound.

By the late 1800s, composers such as Dankó Pista supplied a prolific repertoire that spread through sheet music, songbooks, and early recordings. Professional Roma ensembles standardized the instrumentation—lead violin, cimbalom, kontra, clarinet/tárogató, and bass—and the expressive rubato that became synonymous with the genre. Nóta functioned as both entertainment and a vehicle for patriotic and sentimental expression across the Austro‑Hungarian sphere.

After World War I and II, nóta lived on in restaurant culture, radio, and record catalogues, while tastes shifted toward operetta, schlager, and later popular styles. In the socialist period it persisted as a nostalgic and sometimes ideologically contested music of urban conviviality. International tours by virtuoso prímások carried nóta abroad, where it was often received under the broader label of “Hungarian Gypsy music.”

Today, magyar nóta is both a living tradition and a heritage repertoire. It is celebrated for its virtuosity and emotional immediacy, yet its identity is debated: it is neither identical with rural Hungarian folk song nor reducible to generic “Gypsy music.” Instead, nóta stands at the crossroads of Hungarian popular art song, Roma performance practice, and 19th‑century Central European salon culture.