Hungarian folk music is the traditional music of the Carpathian Basin’s Hungarian-speaking communities, performed for dancing, storytelling, ritual, and everyday social life.

It is characterized by a fiddle-led band (prímás) supported by a three‑string viola (kontra) playing drone-triad shuffles, a double bass (bőgő) marking off‑beats, and often a cimbalom (hammered dulcimer). Melodies frequently use old-style pentatonic and heptatonic modes (notably Dorian and Mixolydian), with rich ornamentation, parlando‑rubato declamation in ballads, and strict tempo giusto in dance tunes. Core dance types include the csárdás (typically a slow lassú followed by a fast friss), verbunk (recruitment dance with dotted rhythms), ugrós, and regional suites from Transylvania (Mezőség, Kalotaszeg, Szék), Gyimes, and Moldva.

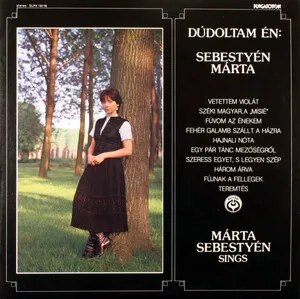

Singing is usually strophic, with narrow-to-moderate ambitus, heterophonic variation between voice and fiddle, and text topics ranging from love and work to historical and humorous narratives. The 20th‑century collection work of Bartók and Kodály, and the late‑20th‑century táncház (dance‑house) revival, helped sustain a living, village-rooted performance practice in urban settings.

Hungarian folk music developed over centuries in the Carpathian Basin, absorbing layers from neighboring peoples and earlier steppe traditions. Older strata show pentatonic contours, narrow ambitus, and parlando‑rubato delivery, while later village dance repertoires moved toward heptatonic modes and stricter rhythms.

By the late 18th century, verbunk (recruitment dance) ensembles popularized dotted rhythms and showy fiddle style, feeding into the 19th‑century csárdás, which paired a slow lassú with a fast friss. Village bands (string-led with kontra and bőgő, sometimes cimbalom) standardized regional dance suites. Urban salon and stage versions circulated widely, often labeled “Gypsy music,” reflecting Romani musicians’ central role as professional performers of Hungarian repertoires.

Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály undertook systematic fieldwork (wax cylinders, later discs), documenting thousands of melodies across Hungary and Hungarian communities in Transylvania and beyond. They distinguished “old style” (parlando, pentatonic) from “new style” (isometric, broader range), and their transcriptions, analyses, and compositions placed village idioms at the heart of modern art music.

Despite urbanization, village bands and singers sustained local styles (Mezőség, Kalotaszeg, Szék, Gyimes, Moldva). Radio and state ensembles presented stylized orchestrations, while community practice preserved rustic bowing, heterophony, and dance-led pacing.

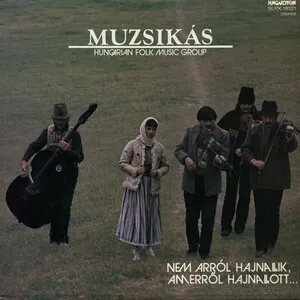

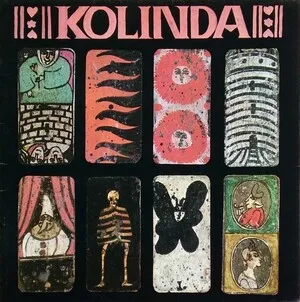

The dance‑house (táncház) movement—spearheaded by musicians like Sebő Ferenc and Halmos Béla—recentered learning on village masters, live dance context, and regional authenticity. Groups such as Muzsikás and Téka made austere, groove‑forward string band sound internationally visible. Today, urban folk clubs, camps, and conservatory programs coexist with village traditions, and younger artists extend the idiom into world, jazz, and even metal contexts without losing core bowing, tuning, and modal practices.