Korean revolutionary opera is a state-directed operatic style that emerged in North Korea during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It fuses Western grand-opera conventions with Korean vocal traditions and a strong collectivist, propagandistic narrative focus.

The genre is defined by stirring mass choruses (often the off‑stage pangchang), singable stanzaic arias in place of long recitatives, easily recognizable leitmotifs, and symphonic accompaniment reinforced by indigenous Korean instruments. Stories portray model workers, soldiers, and party cadres overcoming hardship through revolutionary virtue, with love subplots subordinated to political duty.

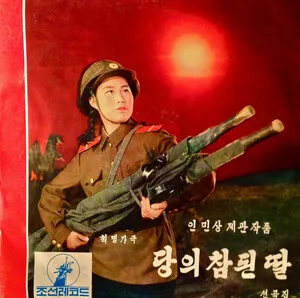

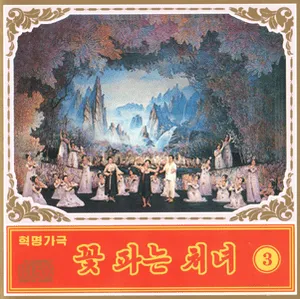

Its canon is epitomized by the Five Great Revolutionary Operas—Sea of Blood, The Flower Girl, A True Daughter of the Party, Tell O Forest!, and The Song of Mount Kumgang—works that set the template for dramaturgy, vocal writing, staging, and ideological messaging within the form.

Korean revolutionary opera arose in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as part of a broader cultural policy that sought to create a "people‑centered" art aligned with revolutionary ideology. Drawing on pre‑existing North Korean stage practices, Western grand opera, and Korean vocal traditions such as pansori, the form coalesced at the end of the 1960s.

The genre’s identity was fixed by the so‑called Five Great Revolutionary Operas: Sea of Blood (1969), A True Daughter of the Party (1971), The Flower Girl (1972), Tell O Forest! (1972), and The Song of Mount Kumgang (early 1970s). These works established key traits: stanzaic arias replacing lengthy recitatives, memorable leitmotifs tied to characters and ideals, large choral interjections (pangchang) that comment on the action, and integrated dance and battle tableaux. Ideologically, they codified narratives of class struggle, anti‑imperial resistance, and devotion to the party.

Under official cultural theory (often attributed to leadership guidance), revolutionary opera emphasized clarity of melody, textual intelligibility, and the fusion of national form with socialist content. Western symphonic forces were combined with Korean instruments to produce a familiar yet distinctly local sound. Dramaturgy favored linear plots with archetypal heroes, rapid scene changes, and ensemble finales exalting collective triumph.

Dedicated troupes—most notably the Sea of Blood Opera Company—premiered and toured these works domestically and abroad, while major art troupes and state ensembles provided singers, orchestral players, and staging resources. Recordings, films, and televised performances reinforced the repertoire and its stylistic norms.

The genre remains a cornerstone of North Korean state performance culture, shaping concert practice, film music, and mass spectacles. Its musical vocabulary—anthemic themes, martial rhythms, and responsive choruses—continues to inform various state ensembles and commemorative productions.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)