Grand opera is a monumental 19th‑century French operatic form defined by large forces, spectacular staging, and serious historical or religious subjects. Typically laid out in five acts, it features extensive choruses, virtuosic arias and ensembles, full ballet sequences (the obligatory "divertissement"), and elaborate scenic effects that turn political and moral conflicts into public spectacle.

Musically, grand opera expands the Romantic orchestra, favors accompanied recitative over secco dialogue, and uses coloristic orchestration, on‑ and off‑stage bands, and crowd scenes to heighten dramaturgy. It emerged at the Paris Opéra (Académie Royale/Impériale) in the late 1820s–1830s through works by Auber, Meyerbeer, and Halévy, and quickly became an international template for large‑scale operatic production.

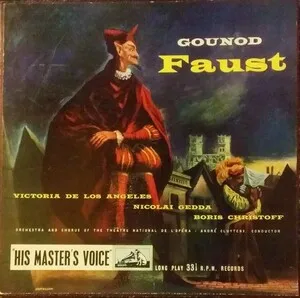

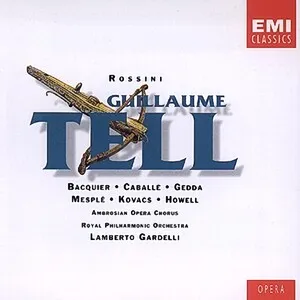

Grand opera crystallized in Paris in the late 1820s, catalyzed by Daniel Auber’s "La Muette de Portici" (1828), Rossini’s French "Guillaume Tell" (1829), and Meyerbeer’s "Robert le diable" (1831). It synthesized the ceremonial grandeur of French Baroque tragédie en musique, the Italianate vocal brilliance of opera seria, the public pageantry of opera‑ballet, and the moral gravitas of the oratorio—now reframed for Romantic audiences and the state‑sponsored Paris Opéra.

Giacomo Meyerbeer became the emblematic figure with "Les Huguenots" (1836), "Le Prophète" (1849), and "L’Africaine" (1865). Fromental Halévy’s "La Juive" (1835) and Auber’s "Gustave III" (1833) consolidated the genre’s conventions: five acts, large mixed chorus, star singers, a mandatory ballet (often Act II/III), elaborate machinery and tableaux, and libretti (often by Eugène Scribe) on historical/religious conflicts rendered as public dramas.

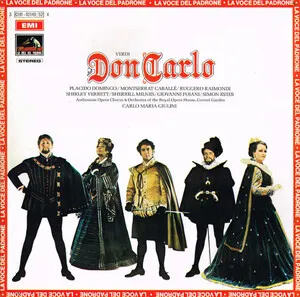

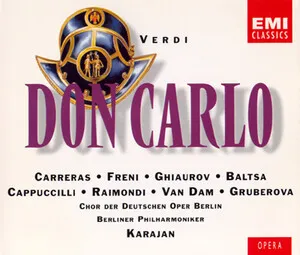

By mid‑century, the grand opera model spread beyond France. Verdi absorbed and retooled it in Paris with "Les vêpres siciliennes" (1855) and "Don Carlos" (1867), integrating Italian lyricism with French scale and ballet requirements. Donizetti ("La Favorite"), Gounod, Berlioz ("Les Troyens"), Thomas, and later Massenet adapted its dramaturgy and orchestral color to diverse aesthetics.

Changing tastes, costs, and the rise of verismo shifted the operatic center of gravity after 1870. Yet grand opera’s innovations—mass scenes, integrated spectacle, expanded orchestration, and political dramaturgy—shaped later opera and modern stagecraft. Since the late 20th century, historically informed revivals and critical editions have restored major works to the repertory, renewing appreciation for the genre’s ambition and theatrical power.

Write for a large Romantic orchestra (expanded winds and brass, harp(s), rich percussion) plus SATB chorus, extra on‑stage and off‑stage bands (banda), and principal/secondary soloists. Plan for a full ballet divertissement with its own orchestral color and dance rhythms.

Structure the work in five acts with accompanied recitative. Alternate public crowd scenes with intimate arias and duets; build toward act‑finales that combine chorus, soloists, and orchestra in climactic concertato writing. Include at least one extended ballet suite and ceremonial processions or marches to articulate large tableaux.

Use a broadly tonal, Romantic idiom with expressive chromaticism and modulatory planning for structural pillars (entrances, revelations, crises). Craft memorable cantabile melodies for arias, but integrate them within through‑planned scenes. Orchestrate for coloristic effect—solo winds for character, brass and percussion for state/public spectacle, off‑stage instruments for spatial drama.

Exploit marching rhythms for ceremonial scenes, dance meters for the ballet, and flexible recitative‑arioso for dialogue. In finales, layer rhythmic ostinati and choral counter‑themes to achieve cumulative intensity.

Choose a historical or religious subject with political stakes and moral conflict—crowd dynamics are central. Write (or set) French verse with clear declamation; collaborate closely with the librettist to align scenic design, stage machinery, and music with narrative beats.

Compose with scenic spectacle in mind: choruses that fill the stage, opportunities for large set changes, and cues for lighting/special effects. Mark on‑/off‑stage placements, processional blocking, and dance interludes explicitly in the score to coordinate musical and visual impact.