Korean folk music (minyo and related traditions) encompasses the vernacular songs, percussion ensembles, narrative epics, and ritual pieces that grew outside the court in villages and marketplaces across the Korean peninsula.

It features cyclic rhythmic patterns (jangdan), pentatonic modal systems such as pyeongjo, ujo, and gyemyeonjo, and distinctive vocal ornamentation (sigimsae) that conveys the affect known as han (a bittersweet, often plaintive sentiment).

Core idioms include minyo (regional folksongs like Arirang), pansori (long-form sung storytelling), sinawi (shamanic-rooted ensemble improvisation), and pungmul/nongak (outdoor farmers’ percussion), performed on instruments such as gayageum and geomungo (zithers), haegeum (spike fiddle), daegeum and piri (flutes/oboes), and the four samul percussion instruments (kkwaenggwari, jing, janggu, buk).

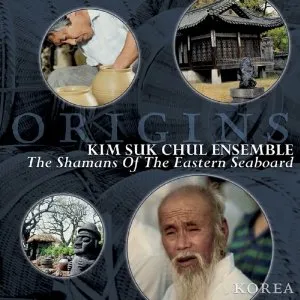

Korean folk music coalesced during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897), drawing on village work songs, shamanic ritual repertories, Buddhist chant, and itinerant entertainers’ arts. While court genres (aak/jeongak) were codified for elite ritual and ceremony, folk practices thrived in agrarian life, markets, and local festivals, gradually forming regional styles of minyo and rhythmic drumming traditions.

By the 17th–18th centuries, narrative epic singing (pansori) emerged, while shamanic-rooted ensemble improvisation (sinawi) and village percussion (pungmul/nongak) became hallmarks of communal life. Modal systems (pyeongjo, ujo, gyemyeonjo) and cyclic rhythmic patterns (jangdan such as jinyang, jungmori, gutgeori, semachi, jajinmori, hwimori) provided shared musical grammar across regions, even as local timbres and dialects diversified the repertory.

In the late Joseon and Korean Empire periods, professional singers and accompanists systematized pedagogy for pansori and instrumental sanjo (a semi-classical solo form birthed from folk idioms). During the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945), folk performance faced censorship and commercialization, yet popular folksongs (e.g., Arirang) circulated widely and became cultural emblems.

After 1945, both Koreas institutionalized preservation in different ways. In the South, the Important Intangible Cultural Properties system recognized masters (ingan munhwajae), sustaining lineages of pansori, minyo, and pungmul. From the late 20th century, concertized formats and ensembles brought folk idioms to theaters and festivals, while recording technologies documented regional styles.

UNESCO inscriptions (e.g., Pansori, Nongak, and various Arirang traditions) boosted international visibility. Since the late 20th century, artists have fused folk timbres and jangdan with jazz, rock, and electronic music, birthing "fusion gugak" and global collaborations while retaining the expressive core—ornamented melody, cyclic rhythms, and narrative voice.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)