Karakalpak traditional music is the folk music of the Karakalpak people, a Turkic ethnic group centered in Karakalpakstan (northwestern Uzbekistan) around the lower Amu Darya and the Aral Sea basin.

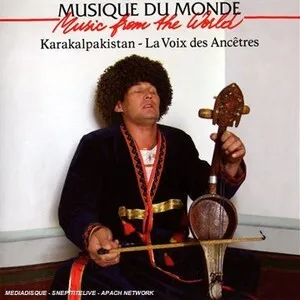

It blends epic recitation (zhyrau/bakhshi) with lyrical songs, dance pieces, and instrumental kúy, performed on regional instruments such as the dutar (two‑string long‑necked lute), gijjak (bowed spike fiddle), qobyz (bowed lyre), doira (frame drum), and jaw harp. Melodically it alternates between pentatonic and heptatonic modal thinking and draws on Islamic/maqām-related melodic sensibilities, while rhythm ranges from free, speech‑like declamation in epics to lively duple or compound meters for dance.

The repertoire preserves oral history, pastoral life, love poetry, and heroic epics like Qyrq Qyz (Forty Girls). Its performance practice is heterophonic and ornamented, with melismas, drones on open strings, and flexible phrasing that follows the cadence of the Karakalpak language.

The Karakalpaks consolidated as a distinct people between the 17th and 18th centuries around the Aral Sea and lower Amu Darya. Their music reflects this frontier environment: epic singing by zhyrau/bakhshi carried genealogies, moral codes, and local histories, while pastoral lyric songs marked the seasonal rhythms of steppe and river life. Instruments such as dutar, qobyz, and gijjak supported both epic narration (often in free rhythm) and dances in duple or compound meters.

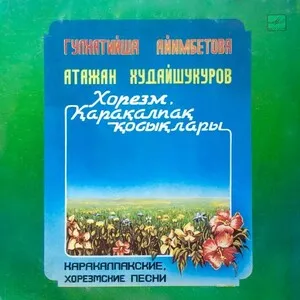

Situated between Khorezm/Uzbek, Kazakh, Turkmen, and Tajik spheres, Karakalpak music absorbed and exchanged modal and formal ideas. Islamic devotional and maqām‑based aesthetics shaped melodic contour and ornamentation, while epic performance shared techniques with neighboring Kazakh and Turkmen zhyrau/bakhshi lineages. Throughout the 19th century, repertories of kúy (instrumental pieces) and narrative cycles were transmitted master‑to‑disciple.

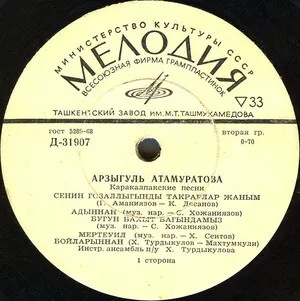

In the Soviet period, collectors and conservatories documented epics, tunes, and instruments, while state folk ensembles standardized concert arrangements for radio and stage. Although these settings introduced choral textures and orchestration, traditional solo epic recitation and small‑ensemble playing persisted in village and family contexts.

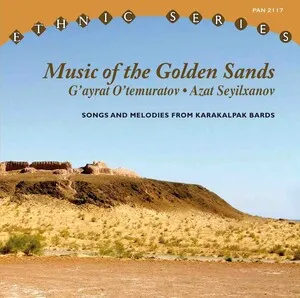

Today, Karakalpak traditional music remains a living practice at weddings, seasonal festivities, and cultural festivals. Epic cycles and lyrical songs continue to be taught orally, while professional ensembles and community arts programs help sustain instrument craftsmanship and transmission amid ecological and social change in the Aral Sea region.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)