Your digging level

Description

Industrial folk song (also called industrial folk music, industrial work song, or industrial working song) is a branch of folk and traditional music that focuses on the lives, risks, and solidarities of industrial laborers.

It typically adapts older folk forms—especially narrative ballads and agricultural work songs—into songs about factories, mines, mills, railways, shipyards, and other industrial workplaces.

Lyrically, it often documents working conditions, class struggle, accidents and disasters, migration for work, unionization, and protest, while musically it tends to remain direct and singable so groups can perform it together in social or organizing settings.

History

Industrial folk song emerged alongside the British Industrial Revolution in the 18th century.

Workers carried familiar vernacular forms—ballads, broadside songs, and rural work-song patterns—into new industrial environments, rewriting themes to fit mill, mine, and factory life.

As industrial labor expanded, similar songs developed in Britain and North America, as well as in France and other industrializing regions.

The repertoire grew around specific industries (coal mining, textile mills, railroads, maritime labor), and songs increasingly served as oral records of dangers, wages, bosses, and community life.

With the rise of organized labor, industrial folk songs became tools for solidarity and protest, spreading through unions, strikes, and worker organizations.

They often blended documentation with persuasion—aimed at recruitment, morale, and public sympathy.

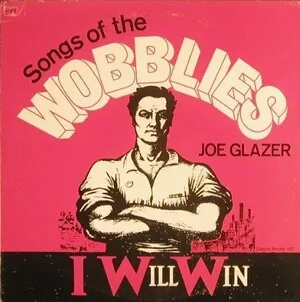

Folk collectors, singers, and revivalists recorded and popularized industrial songs, preserving regional variants and bringing worker narratives to wider audiences.

This period strengthened the genre's association with labor causes and political song.

Modern performers continue to write new industrial songs (or recontextualize older ones) about deindustrialization, precarious labor, and new workplace realities.

While the sound may overlap with singer-songwriter and protest traditions, the defining feature remains the industrial worker subject matter and communal singability.

How to make a track in this genre

Write from the perspective of industrial workers or their communities, focusing on concrete details: tools, shifts, hazards, wages, and names of places.

Use a clear narrative arc (incident → consequence → reflection/call-to-action) or a repetitive work-chant structure suitable for group singing.

Choose simple, memorable melodies with limited range so non-professional singers can join.

Common forms include strophic ballads (same melody each verse) and call-and-response, which supports communal performance.

Keep rhythm steady and functional, often mirroring repetitive labor.

Moderate tempos and strong downbeats work well; if using a work-song feel, emphasize a pulse that could align with coordinated movement.

Use straightforward diatonic harmony (often I–IV–V) or modal folk harmony.

Avoid dense chord changes; the genre benefits from harmonic stability so lyrics remain central and choruses are easy to remember.

Emphasize authenticity and specificity.

Common topics include workplace danger, exploitation, pride in craft, migration for work, solidarity, strikes, and remembrance of industrial disasters.

If writing a protest-oriented piece, include a chorus that states demands or unifies the group (short, repeatable, emotionally direct).