Hill tribe music refers to the traditional musics of the highland ethnic groups of Northern Thailand (notably Hmong, Karen, Lisu, Lahu, Akha, and Mien/Yao). It is largely oral, community-centered, and tied to animist ritual cycles, agricultural calendars, courting traditions, and seasonal festivals.

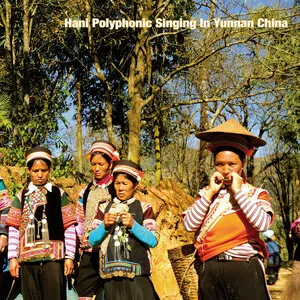

Common timbres come from bamboo and wood: free-reed mouth organs (e.g., Hmong qeej and related lusheng types), end-blown and transverse flutes, jaw harps, frame and barrel drums, small gongs, clappers, and various plucked lutes. Melodies often draw on anhemitonic pentatonic scales, with flexible rhythm that follows text and dance rather than strict meter. Vocal styles range from antiphonal courting songs and heterophonic group singing to chant-like ritual recitations.

While each community has distinct repertoires and performance practices, the shared highland sound emphasizes portability, breath-driven reeds and flutes, cyclic grooves for dancing, and music as a vehicle for social memory, storytelling, and spiritual mediation.

Hill tribe music coalesced in its present Northern Thai context as various highland communities (Hmong, Karen, Lisu, Lahu, Akha, Mien/Yao) migrated into the region during the 18th–19th centuries. Though the musical roots are far older, the 1800s mark the period when distinctive repertoires, instruments, and ritual uses took shape in the Thai highlands. Music functioned as a living archive for oral histories, agricultural knowledge, and animist cosmologies.

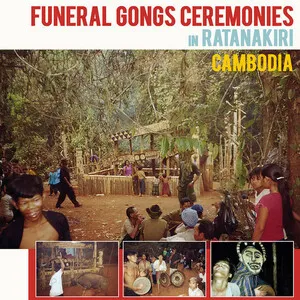

Free-reed mouth organs (e.g., Hmong qeej), bamboo flutes, jaw harps, hand drums, and small gong sets became core media for courtship songs, spirit-invoking ceremonies, harvest and new-year festivals, and communal dances. Scales are often pentatonic; textures are heterophonic; and form is cyclic, designed for processions and social dancing. Lyrics transmit ancestral narratives, ethical teachings, and place-based lore.

From the 1950s onward, ethnographers and broadcasters recorded village ensembles and festival performances, introducing hill tribe music to archives and radio. Missionization, schooling, tourism, and state integration created new performance contexts and hybrid repertoires (festival stages, cultural centers, and schools) while some ritual pieces retreated from public use.

Since the 1990s, field recordings, cultural festivals, and heritage programs have supported transmission to younger generations. Urban and global audiences encounter hill tribe sounds through documentaries and world/ambient producers sampling mouth organs and flutes. Within communities, music remains central to rites of passage, agricultural cycles, and identity, even as amplified setups and staged performances become more common.