Your digging level

Description

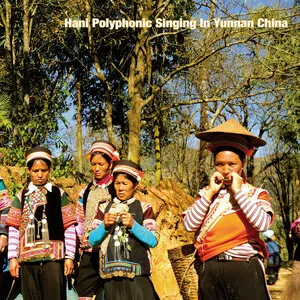

Hill tribe music refers to the traditional musical practices of highland ethnic communities living across Northern Thailand and the adjoining uplands of mainland Southeast Asia. Core groups include Hmong (Miao), Karen (Sgaw and Pwo), Lahu, Lisu, Akha, Mien (Yao), Khmu, H’tin, Wa, Kachin and others. While each group maintains distinct repertoires, instruments, and vocal aesthetics, they share features such as bamboo aerophones and idiophones, pentatonic-centered scales, heterophonic textures, and performance contexts tied to agricultural cycles, courtship, household rituals, ancestor veneration, and communal festivals.

Characteristic instruments include bamboo free-reed mouth organs (e.g., Hmong qeej and related lusheng types), gourd flutes (hulusi), end-blown and duct flutes, jew’s harps, leaf instruments, frame and log drums, small gong sets, and lutes. Vocal music ranges from unmetered, speech-tone–shaped recitative to responsorial dance songs. Melodic organization often follows anhemitonic pentatonic patterns, with flexible meter and rhythmic cycles shaped by dance steps rather than by strict percussion patterns.

History

Hill tribe music emerged from the ritual, agricultural, and social life of highland communities whose histories span the Yunnan–Indochina uplands. Musical functions encompassed ancestor rites, healing and shamanic ceremonies, seasonal festivals (such as New Year), courtship, and communal storytelling. Instruments developed from available materials—especially bamboo and gourds—leading to a strong aerophone and idiophone profile.

From the late 1700s into the 1900s, waves of migration brought Hmong, Lisu, Lahu, Akha, Mien, and others south from southern China into today’s Northern Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar. In new settlements, music continued to encode language tones, clan history, and myth cycles, while also absorbing elements from neighboring Tai/Kadai, Mon–Khmer, and Burmese traditions. Pentatonic scales, heterophony, and free-rhythm solo song remained core, even as gong practices, dance forms, and some song genres reflected intercultural contact.

Colonial, postcolonial, and ethnographic projects in the 20th century produced field recordings and notations of hill tribe repertoires. State and NGO cultural programs in Thailand later promoted festival stages and community ensembles to safeguard intangible heritage. Despite pressures from modernization, schooling, and out-migration, transmission through apprenticeship (e.g., qeej masters, ritual singers) persists in villages and diaspora communities.

Today, traditional ensembles perform at rituals and festivals, while youth experiment with hybrid forms (e.g., pairing hulusi or jew’s harp with guitar, or integrating pentatonic melodies into folk-pop and world-fusion contexts). Community media and online platforms have helped circulate both archival recordings and new interpretations, sustaining continuity alongside innovation.