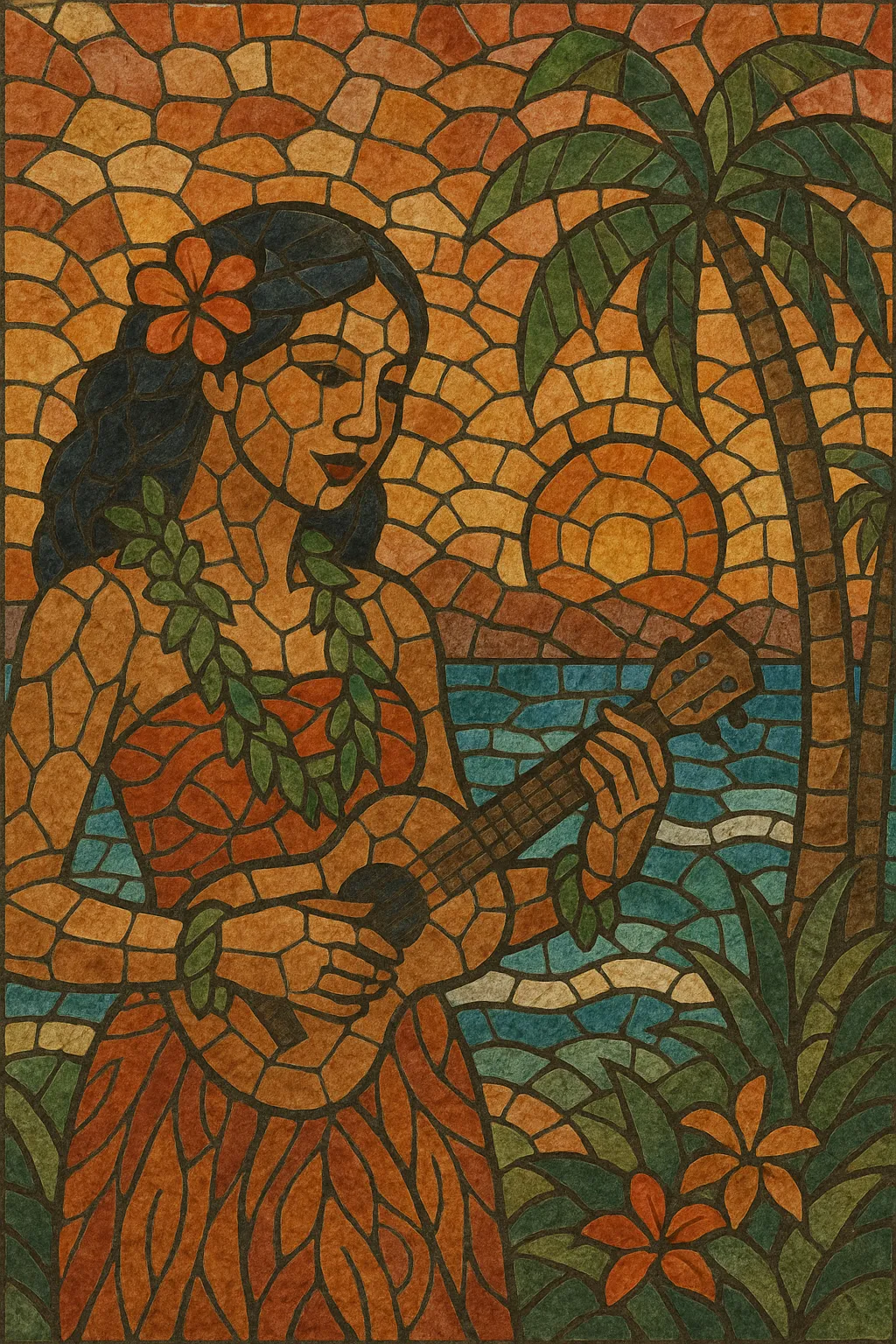

Hapa haole is a style of Hawaiian popular song that blends English-language lyrics (often peppered with Hawaiian words and place names) with the melodies, harmonies, and song forms of early 20th‑century American popular music. Typically arranged for ukulele, guitar, and Hawaiian steel guitar—often with rhythm‑section and light horn or reed parts—it presents an easygoing, danceable feel designed for hotel showrooms, radio, and ballrooms.

The genre romanticizes island life with themes of aloha, hula, leis, surf, and Waikīkī sunsets, set to Tin Pan Alley’s verse–chorus or AABA forms and light jazz/swing rhythms. It became a bridge between Native Hawaiian musical elements and mainland U.S. pop sensibilities, producing enduring standards that still surface in hula shows and vintage lounge repertoires.

Hapa haole emerged in the early 20th century as Hawaiʻi’s musical culture encountered mainland U.S. entertainment circuits. After annexation (1898) and the growth of tourism, composers and bandleaders in Honolulu and Waikīkī adapted hotel and dance‑band formats to local tastes. The 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco helped popularize the ukulele and steel guitar on the mainland, accelerating demand for “island” songs in English. Arrangers like Johnny Noble codified the mix of Hawaiian instrumentation and Tin Pan Alley forms, giving rise to a distinctive “half‑foreign” (hapa haole) sound.

Radio (notably the long‑running "Hawaii Calls" program starting in 1935), Hollywood musicals, and Waikīkī showroom bands propelled the style worldwide. Songwriters such as R. Alex Anderson and Harry Owens supplied enduring repertoire (e.g., “Lovely Hula Hands,” “Sweet Leilani”), while performers like Sol Hoʻopiʻi and Andy Iona blended virtuosic steel guitar with light swing. The music’s easy lilt, lush imagery, and crooning vocals fit seamlessly into the era’s big‑band and popular song aesthetics.

As mid‑century tiki culture blossomed, hapa haole standards fed lounge and exotica repertoires on the mainland. Singers such as Alfred Apaka and Don Ho brought a polished, nightclub‑ready sheen, while hotel orchestras and resort shows cemented the genre’s association with hospitality and tourism. Though increasingly stylized, the core blend—Hawaiian instruments, English lyrics, and Tin Pan Alley craft—remained intact.

During the Hawaiian Renaissance, some critiqued hapa haole’s commercialized imagery, preferring native‑language genres and traditional practices. Yet many hapa haole songs endured as hula standards and nostalgic favorites. Today the style appears in vintage lounge sets, heritage festivals, and curated recordings, appreciated both as a historical bridge in Hawaiian–American popular music and as a living repertoire for dancers and bands.