Greenlandic music encompasses the traditional and contemporary musical practices of Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland), spanning Inuit drum-dance songs (qilaatersorneq/ajaajaa), Moravian/Lutheran hymn and choral traditions, and modern popular styles such as rock, pop, folk, reggae, and hip hop.

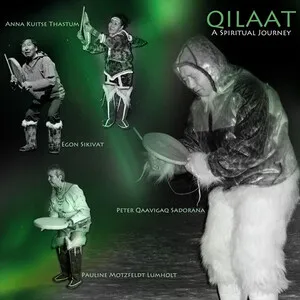

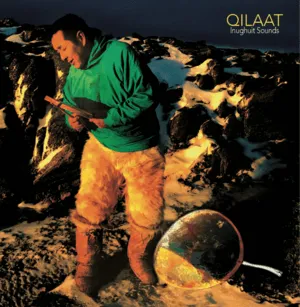

At its core are communal, vocable-rich songs accompanied by the frame drum (qilaat), storytelling lyrics about environment and daily life, and call-and-response performance practices. Since the 18th century, missionary hymnody introduced four-part choral singing and European tonal harmony, which blended with local practices.

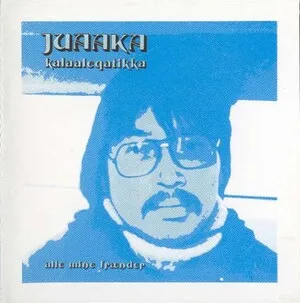

From the 1970s onward, Greenlandic-language rock and pop became a vehicle for cultural identity and political expression, with bands like Sume shaping a distinctive sound that remains influential. Today, artists mix drum-dance timbres, hymn-like harmonies, and global genres while foregrounding lyrics in Kalaallisut and themes of place, language, and community.

Greenlandic music is rooted in Inuit musical practices that long predate written documentation. Central are drum-dance songs (qilaatersorneq) performed with a frame drum (qilaat) and vocable-led melodies often called ajaajaa. These songs are communal and narrative, used for celebration, social regulation, humor, and recalling events or places. Melodies are typically narrow in range, with flexible rhythm supported by steady drumming and audience participation.

From the early 1700s, Danish-Norwegian and Moravian missionaries introduced hymn singing, organs, and European notation. Moravian/Lutheran chorales fostered community choirs and four-part harmony, leaving a lasting choral tradition that blended with local aesthetics. This period also led to documentation of indigenous songs and the emergence of distinct regional variants (West, East, and North Greenland) within a shared Greenlandic identity.

In the mid-20th century, radio and record production helped circulate both traditional music and new styles. By the 1960s–1970s, Greenlandic-language rock crystallized as a cultural force. Sume’s politically charged records connected global rock idioms to Greenlandic self-determination, inspiring subsequent generations. Independent labels and community infrastructure broadened access, while hymn and choir practices continued in churches and schools.

Popular music diversified into pop, folk, reggae-inflected rock, and hip hop. Acts such as Nuuk Posse brought Greenlandic rap to the fore; singer-songwriters and indie bands gained international attention, often singing in Kalaallisut and English. Festivals and local media sustained a vibrant scene that balanced tradition with contemporary production.

Contemporary Greenlandic music is plural: drum-dance performances, choirs, rock bands, indie-folk ensembles, and hip hop crews all coexist. Artists frequently reference landscape and language, incorporate the timbre of the qilaat, and draw on hymn-like harmonies, while leveraging modern recording tools and global collaboration to reach wider audiences.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)