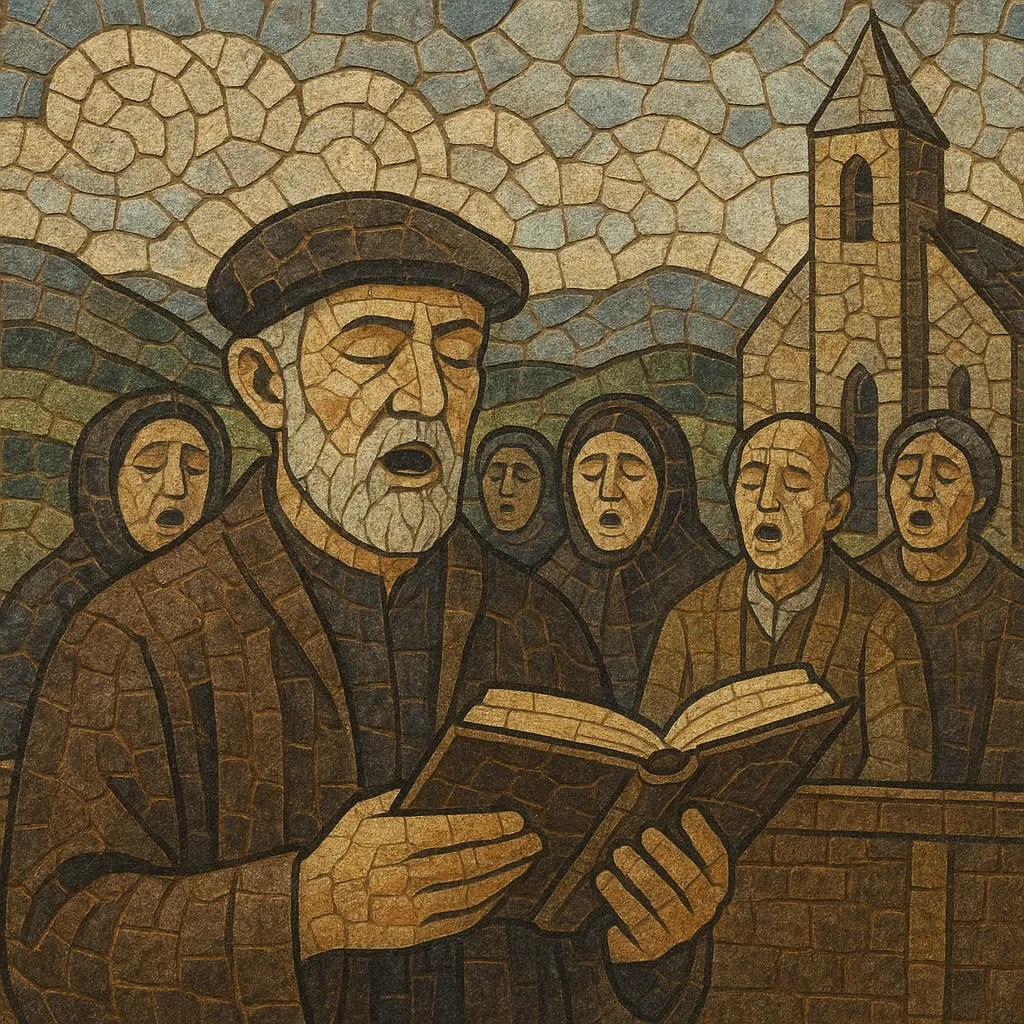

Gaelic psalm singing (Salm Gàidhlig) is an a cappella congregational singing tradition of the Scottish Highlands and Hebrides, especially within Presbyterian churches. A precentor “lines out” each verse line of a metrical psalm, and the congregation answers in a free, highly ornamented, and heterophonic style.

The sound is slow, modal, and intensely communal: individual voices bend pitch, slide between notes, and add melismas while moving at slightly different speeds, creating a shimmering, choral tide. Performances are typically unaccompanied, in Scottish Gaelic, and take place in worship rather than concert settings.

While rooted in Reformation-era metrical psalmody, the style bears the imprint of Gaelic vocal aesthetics, producing a uniquely solemn, devotional, and emotionally expansive texture.

Following the Protestant Reformation, Scottish Presbyterian worship adopted metrical psalmody so congregations could sing scriptural texts in their own language. In Gaelic-speaking regions, psalms were translated into Scottish Gaelic and sung using “lining-out,” a practice where a precentor intones each line for the congregation to repeat. Limited access to printed books and varying literacy levels made lining-out essential, while the local Gaelic vocal style—ornamented, melismatic, and flexible—shaped how the responses sounded.

As Lowland churches increasingly moved toward regular choirs, organs, and harmonized hymnody, Gaelic-speaking parishes in the Highlands and islands (especially Lewis and Harris) retained the older, unaccompanied, heterophonic approach. The repertory centered on metrical psalm tunes in common meters (e.g., Common Meter), but the delivery remained slow, modal, and deeply expressive, with the precentor guiding pitch, pace, and textual emphasis.

The tradition continued most strongly in the Free Church and Free Presbyterian Church congregations. Scholars and fieldworkers associated with the School of Scottish Studies, among others, documented services and precentors, noting the singularity of the sound world and its community function. Although Gaelic language shift and changing worship practices affected prevalence, the style remained a living devotional practice in key communities.

Recordings, documentaries, and curated projects (e.g., ensemble-based presentations of Lewis psalm singing) introduced the wider world to the sound. Ethnomusicologists have explored links between Gaelic lining-out and parallel practices in early American and African American congregational singing. Today, the style endures in its home communities and appears in cultural events and collaborative projects that respectfully frame it for audiences beyond the church.

Gaelic psalm singing stands as both sacred practice and sonic emblem of Gaelic identity, exemplifying how local aesthetics inflect a pan-Reformation worship form. Its communal heterophony and intense expressivity have made it an important reference point in discussions of congregational singing across the Atlantic world.