Celtic chant is an early medieval plainchant tradition associated with the insular (Irish and, to a lesser extent, British) Celtic Christian rites before the widespread adoption of the Roman-Frankish (Gregorian) liturgy. It is monophonic, unaccompanied, and modal, using free, speech-like rhythm shaped by the natural accents of Latin liturgical texts.

Most of its musical corpus is lost; what survives are primarily texts (e.g., the Antiphonary of Bangor) and a small number of melodies preserved in adiastematic neumes (e.g., in the Stowe Missal) that require scholarly reconstruction. Nevertheless, its surviving traits suggest a chant style closely related to other Western plainchant families of the period (Gallican, Ambrosian), while reflecting distinctive insular literary and liturgical sensibilities.

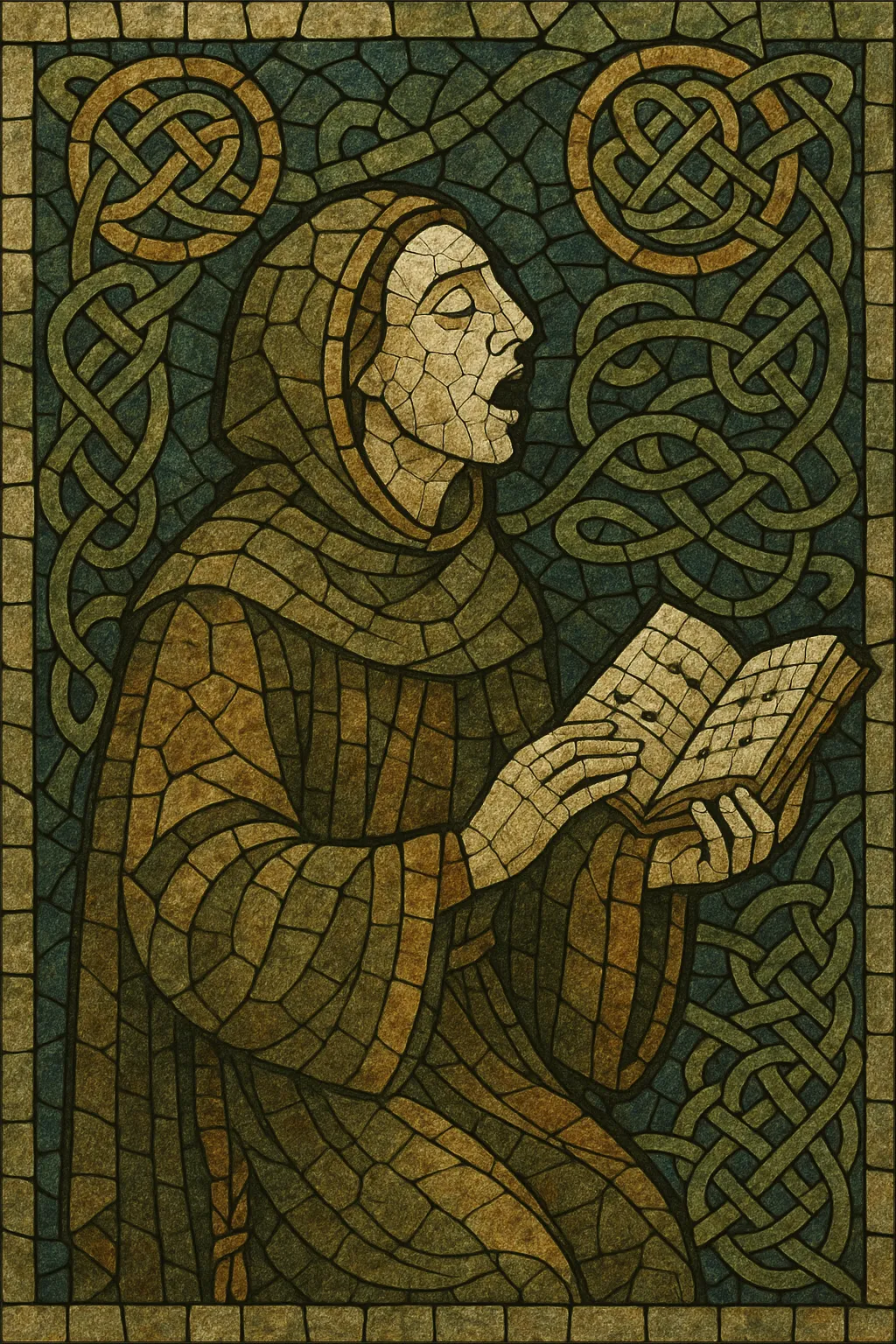

Celtic chant emerged in the early medieval period within Irish monastic culture and related insular communities, reaching recognizable form by the 7th century. Monasteries such as Bangor and Iona served as hubs for liturgical creativity, producing Latin hymnody and chant that accompanied a distinctive Celtic rite.

The Antiphonary of Bangor (late 7th century) preserves a large body of texts that document the range of Celtic liturgical practice, though it transmits little melodic information. Musical notation for the tradition survives sparsely, most notably in the Stowe Missal (late 8th–early 9th century), where adiastematic neumes indicate melodic contour without precise pitch—requiring comparative reconstruction using related Western chant traditions.

Celtic chant developed alongside Gallican, Ambrosian, and other local rites. While sharing the fundamental features of Western plainchant—monophony, modality, and centonized melodic formulas—it displays insular textual styles (e.g., lorica hymns) and distinctive psalmody practices. During the Carolingian reforms (8th–9th centuries), Roman chant, synthesized with Gallican elements, crystallized into what we now call Gregorian chant. The Celtic rite was progressively replaced, and much of its melodic repertory vanished.

By the 11th–12th centuries, the Roman (Gregorian) liturgy had largely supplanted Celtic liturgical use across Ireland and Britain. The legacy of Celtic chant survives in a handful of neumed sources, in poetic and devotional texts, and in the broader insular contribution to Western chant culture. Modern scholarly editions and historically informed performers have attempted cautious reconstructions, and contemporary sacred and "Celtic new age" projects sometimes draw inspiration from its modal, meditative ethos.

From the 20th century onward, chant scholarship (paleography, modality studies) and early-music performance practice have brought renewed attention to non-Gregorian Western chant families. Although the Celtic repertory remains fragmentary, recordings and research have helped contextualize it within the diverse plainchant landscape of early medieval Europe.