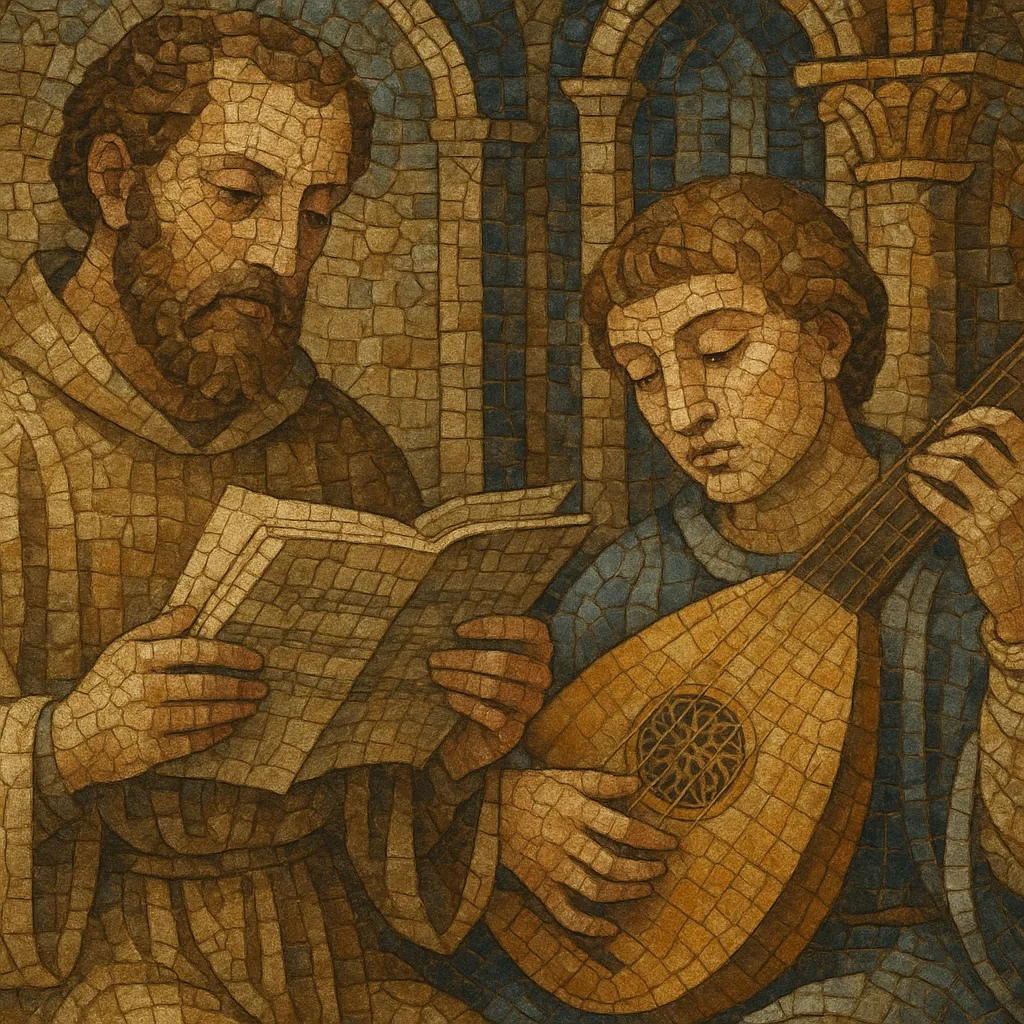

The Franco-Flemish School refers to a succession of Northern European composer-singers from the Low Countries and northern France who, during the 15th and 16th centuries, perfected a richly woven style of vocal polyphony.

Centered on sacred forms such as the Mass and motet, and on courtly chansons, their music is characterized by careful control of dissonance, modal counterpoint, cantus-firmus and paraphrase techniques, and—by the later generations—pervasive imitation. Their chapel-trained composers staffed the great courts and cathedrals of Europe and spread a unified, technically rigorous polyphonic practice from Burgundy and the French royal chapels to Italy, Spain, the Empire, and beyond.

The style emerges from the Burgundian and Netherlandish musical milieu, inheriting techniques from Ars antiqua and Ars nova and the refined rhythmic/contrapuntal play of Ars subtilior. Cantus-firmus technique over plainchant (Gregorian chant) underpins early Mass cycles and motets, while courtly chansons maintain the heritage of formes fixes.

Composers such as Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois bridge Burgundian practice and the emerging Franco-Flemish language. Antoine Busnoys and Johannes Ockeghem deepen the idiom with expanded vocal ranges, supple rhythmic flexibility, and sophisticated canon and mensuration.

Josquin des Prez becomes the emblematic figure: clear formal articulation, pervasive imitation between voices, and text-sensitive writing shape both Mass and motet. Music printing (e.g., Petrucci’s early 1500s editions) accelerates the dissemination of the Franco-Flemish sound across Europe.

Adrian Willaert at San Marco in Venice adapts Netherlandish counterpoint to Italian taste, influencing madrigal writing and antiphonal textures. In Spain and the Habsburg realms, Franco-Flemish composers (e.g., Pierre de La Rue) anchor court chapels, strengthening a transregional sacred style.

Nicolas Gombert and Jean Mouton intensify imitative density and continuous textures, while Jacob Obrecht refines paraphrase and cantus-firmus Masses. Orlande de Lassus synthesizes cosmopolitan idioms—sacred and secular—in multiple languages, effectively closing the Renaissance with an authoritative polyphonic voice.

The school codifies modal counterpoint, imitation, and cadential grammar that become the backbone of European choral tradition. Its contrapuntal methods flow into Italian madrigals and ultimately inform Baroque and later Western classical practice.