Your digging level

Description

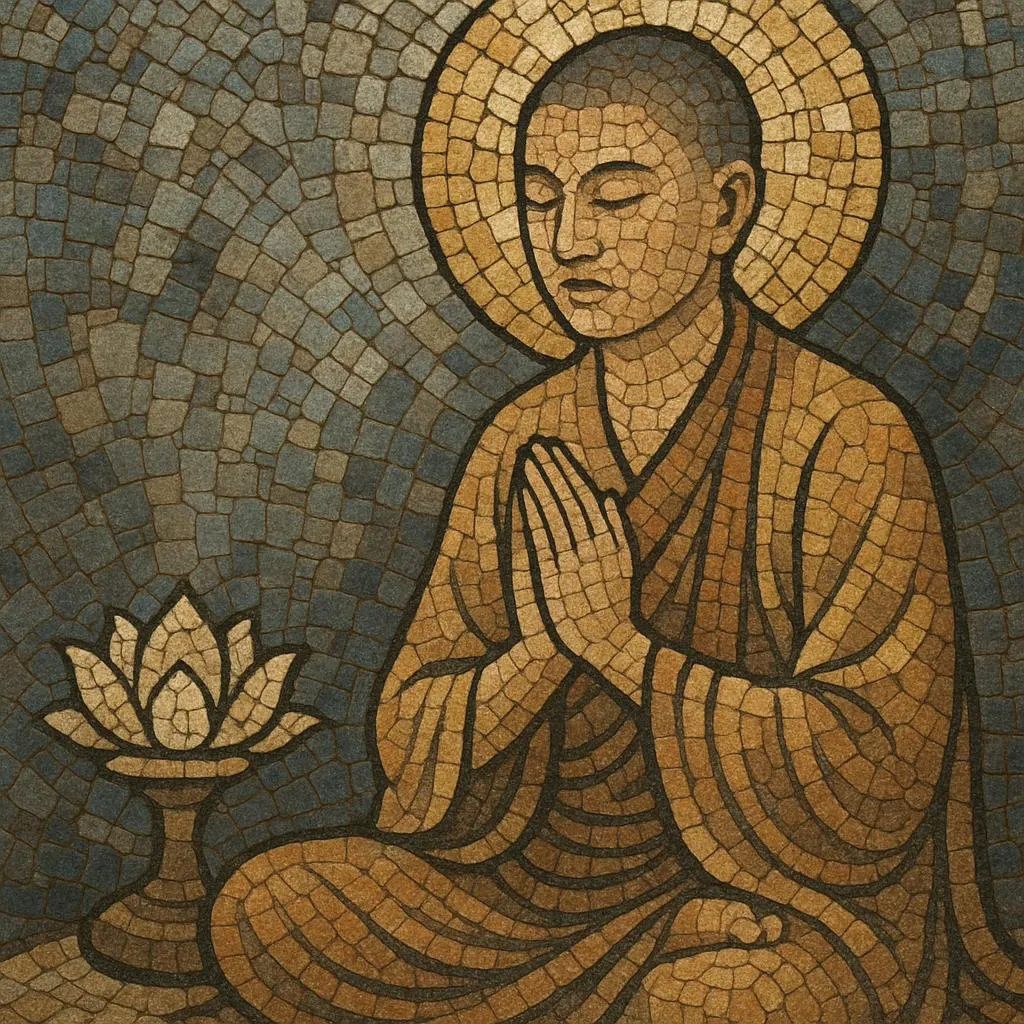

Fo jing is a Chinese Buddhist devotional music tradition centered on sung and chanted renditions of sutras (佛经), dhāraṇīs, and mantras. It typically presents liturgical texts in Classical Chinese, often interwoven with Sanskrit or Pali seed syllables, and is performed in Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien/Min Nan, or other Sinitic varieties.

Musically, fo jing balances austere, syllabic recitation with gentle melodic contours drawn from Chinese pentatonic practice. Performances range from unaccompanied monastic chant to arrangements with temple percussion (wooden fish/mùyú, small bell/qìng, hand cymbals, frame drum, gong) and, in modern recordings, subtle drones, strings, or synthesizer pads. The affect is meditative and reverent—used for worship, memorization of scripture, funerary rites, and personal contemplation—while remaining text-forward so that the sacred words remain intelligible.

Sources: Spotify, Wikipedia, Discogs, Rate Your Music, MusicBrainz, and other online sources

History

Buddhist scripture recitation entered China along with Buddhism in the Han–Wei periods and matured liturgically by the Sui–Tang dynasties (600s–900s). As monasteries systematized ritual, Chinese tonal prosody and pentatonic sensibilities shaped how sutras and dhāraṇīs were intoned, yielding distinctive Han-Chinese chant styles apart from Indian Vedic recitation and later Japanese shōmyō.

Across the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing eras, monastic communities codified repertoires for daily services, memorials, and feast days. Performance practice emphasized unison or heterophonic chant led by a cantor (făshī), with responsorial or processional sections supported by temple percussion. Regional variants (Mandarin- and Cantonese-area temples, coastal Hokkien traditions, mountain pilgrimage centers) preserved local melodic turns while maintaining a core devotional ethos.

In the 20th century, radio and records documented temple ensembles and popularized major texts (e.g., the Heart Sutra, Great Compassion Mantra). Post‑1970s, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and later mainland China saw a flourishing of studio fo jing: producers paired venerable chant with unobtrusive harmonium-like drones, strings, and soft electronics that suited meditation and home devotion.

Since the 1990s, Chinese diaspora communities and digital platforms spread fo jing globally. Contemporary releases balance liturgical authenticity (clear diction, canonical pacing) with accessible timbres for wellness, mindfulness, and educational contexts. While concert versions exist, the genre’s center remains devotional utility: preserving scripture through sound and cultivating calm, compassionate attention.