European free jazz is a post-1960s jazz current that transplanted the freedoms of American free jazz into European contexts while developing its own aesthetic priorities. It privileges collective improvisation, timbral exploration, and open form over chord-based harmony and fixed meter.

Compared to its American counterpart, European free jazz tends to be less blues- and gospel-derived and more informed by the European avant‑garde: contemporary classical techniques, serial and post-serial thinking, graphic notation, extended instrumental techniques, and experimental approaches to sound and silence. It spans intense, high-energy "fire music" as well as sparse, textural improvisation, and thrives in both small groups and large ensembles.

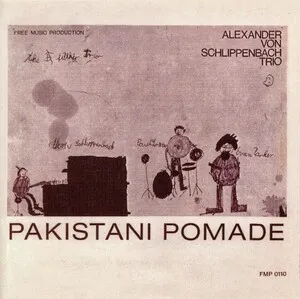

The scene coalesced across Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, France, and Poland, supported by independent labels and festivals (FMP, Incus, BYG/Actuel, ECM, ICP), and by collectives that treated improvisation as both an artistic practice and a social project.

European free jazz emerged as musicians across Europe absorbed the radical improvisational freedoms introduced by American free jazz while drawing on local musical and intellectual traditions. Early catalysts included visiting Americans (e.g., Don Cherry, Steve Lacy) and pioneering Europeans who sought independence from bop and modal frameworks. By the mid-to-late 1960s, landmark recordings such as Peter Brötzmann’s Machine Gun and the activities of UK, German, Dutch, and Scandinavian players signaled a distinct European approach.

Where American free jazz often retained blues inflection and a flexible swing feel, many European players leaned toward abstraction: textures over tunes, sound-mass over chord changes, timbre and extended techniques over orthodox phrasing. Influences from European contemporary classical music (serialism, aleatoric methods, musique concrète, graphic scores) and from regional folk traditions informed this aesthetic. Large ensembles like the Globe Unity Orchestra framed improvisation within shifting, sometimes conducted, structures.

The 1970s saw infrastructure that sustained the scene: Berlin’s FMP, the UK’s Incus, the Dutch ICP collective, France’s BYG/Actuel, Switzerland’s HatHut, and Germany’s ECM (which, while broader in scope, documented crucial strands of European improvisation). Festivals and alternative venues created transnational networks, and collectives experimented with self-organization, DIY production, and new audience contexts.

European free jazz diversified: some streams emphasized energy music and noise-adjacent intensity; others pursued spacious, chamber-like interplay and silence. Musicians collaborated across borders and with dancers, poets, and theater companies; they also interfaced with free improvisation, avant-prog, experimental rock, and electroacoustic practices. Educational programs and workshops helped transmit techniques to younger generations.

Today the tradition remains vibrant, with festivals, labels, and ensembles across Europe. The music’s influence is audible in modern creative jazz, chamber jazz, improvising large ensembles, and experimental scenes that foreground texture, process, and collective interaction. European free jazz is less a fixed style than a methodology: listening-forward, structurally open, and committed to sonic exploration.