Your digging level

Description

Ethio-jazz is a hybrid style that fuses Ethiopian modal systems (qenet) with the language of jazz, funk, and soul. Its core sound draws on pentatonic Ethiopian modes such as tizita, bati, ambassel, and anchihoye, set over hypnotic grooves and spacious, modal harmony.

Characterized by warmly overdriven horns, vibraphone, electric piano/organ, guitar, and supple bass-and-drum vamps, Ethio-jazz tends to favor mid-tempo, trance-like feels, asymmetrical and compound meters, and a melancholic, minor-key atmosphere. Improvisation follows jazz practice, but melodic shapes, ornamentation, and phrasing reflect Ethiopian traditions.

The result is music that feels simultaneously ancient and modern—rooted in Addis Ababa’s club scene of the late 1960s/early 1970s yet timeless in its modal lyricism and cinematic mood.

History

Ethio-jazz crystallized in Addis Ababa in the 1960s, led by vibraphonist, composer, and arranger Mulatu Astatke after studies in London and New York. Returning to Ethiopia, he began blending Ethiopian qenet (modal systems such as tizita, bati, ambassel, anchihoye) with jazz harmony, Afro‑Cuban/Latin rhythms, and the funk/soul grooves he encountered abroad. Early bands and hotel orchestras in Addis—often featuring saxophones, trumpets, guitar, organ, bass, and drums—became the laboratory for this synthesis.

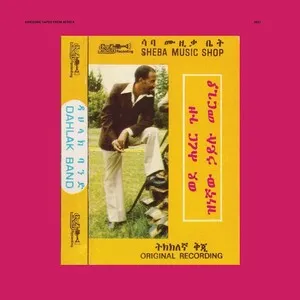

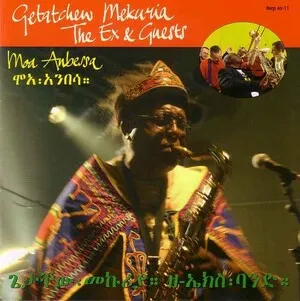

The early 1970s saw a flowering of studio and club activity around labels like Amha Records and Kaifa. Landmark sides by Mulatu Astatke (e.g., Ethiopian Modern Instrumentals Vol. 5), saxophonists like Getatchew Mekuria, pianist/arranger Girma Bèyènè, and ensembles such as The Walias Band defined the sound: modal vamps, moody horns, vibraphone and organ textures, and improvisations informed by both hard bop and Ethiopian melodic language.

After the 1974 revolution and the rise of the Derg regime, nightlife and recording diminished. Many musicians emigrated; The Walias Band’s U.S. tour led key members (including Hailu Mergia) to settle abroad. Ethio‑jazz survived in diaspora pockets and in hotel gigs but largely receded from international attention.

The Buda Musique Ethiopiques reissue series in the late 1990s reintroduced global audiences to classic Ethiopian recordings, with volumes devoted to Mulatu and contemporaries catalyzing a major revival. Film placements (notably Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers in 2005) and collaborations (Mulatu with The Heliocentrics; Either/Orchestra with Ethiopian legends) propelled the style into festivals and conservatories. A new generation—Hailu Mergia’s comeback, Debo Band, Samuel Yirga, Jorga Mesfin—extended the idiom.

Ethio-jazz is an international touchstone for modal groove and cinematic mood. It is sampled by hip-hop beatmakers, adapted by nu‑jazz and world‑fusion ensembles, and sustained by Ethiopian and diaspora musicians who continue to explore the qenet within contemporary jazz frameworks.