Csángó folk music is the traditional music of the Csángó (Csángó-magyar) people, a Hungarian-speaking Catholic minority living mainly in Moldavia (eastern Romania) and in some Eastern Carpathian valleys. It preserves unusually archaic melodic types, ballads, and devotional songs alongside vigorous dance tunes used for village festivities.

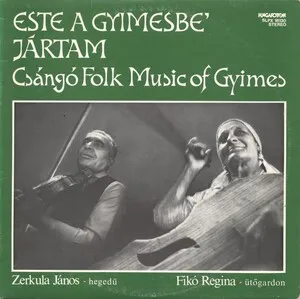

The style features modal melodies (often pentatonic, Dorian, and Aeolian), narrow ambitus tunes with formulaic ornaments, and strong rhythmic drive suited to circle and couple dances. Typical instruments include fiddle (prím), koboz (a lute used for rhythmic-drone strumming), flutes (furulya, kaval), and frame/drums; unaccompanied or heterophonic group singing is common in ballads and religious repertoires. Dance sets such as the “sirülő,” “hétlépés,” and “kettős” are emblematic, performed at brisk tempos with punchy bowing and percussive koboz strums.

Csángó folk music grew in relative isolation in Moldavia (present-day Romania), where Hungarian-speaking Catholic communities conserved pre-modern melodic types, medieval ballads, and Latin-liturgical song traditions. The repertoire blends archaic Central/Eastern European village dance music with Catholic chant, resulting in a distinctive coexistence of sacred and secular practice.

From the late 19th century and especially the early 20th century, Hungarian collectors and composers (notably Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, and later László Lajtha) documented Moldavian and Gyimes Csángó repertoires. Their fieldwork revealed pentatonic “old style” tunes, modal ballads, and a dance band sound centered on fiddle and koboz. These findings shaped broader understandings of Hungarian and Carpathian folk strata.

Under socialist Romania, migration, modernization, and cultural policy reduced traditional contexts, but village practice persisted. After 1989, a strong revival blossomed via the Hungarian táncház (dance-house) movement, urban folk ensembles, and festivals. The táncház safeguarding model—recognized by UNESCO—helped circulate Csángó tunes, dances, and instruments to new generations in Hungary and across Europe.

Today, village tradition-bearers and professional/semiprofessional ensembles perform Csángó repertoires on stages and in community dance events. Festivals in Romania and Hungary spotlight Csángó culture; recordings and workshops sustain transmission, and the style continues to inform world/folk-fusion projects while remaining rooted in village dance functions.