Your digging level

Description

A concerto for orchestra is a 20th‑century orchestral genre that treats the entire orchestra as the virtuoso "soloist." Instead of spotlighting a single instrument against an accompaniment, it rotates concertante roles among sections and individual players, showcasing color, agility, and technical brilliance across the ensemble.

While it inherits structural rigor from the symphony and concerto grosso, the genre favors vivid orchestration, sectional solos, and a sense of theatrical display. Composers often use variation, fugal, or arch‑like forms to balance spectacle with architectural coherence.

History

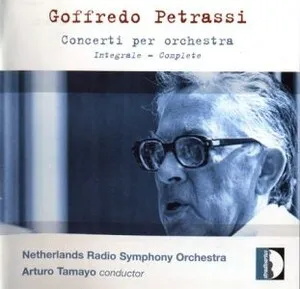

Early examples of works explicitly titled “Concerto for Orchestra” emerged in interwar Europe, as composers sought new ways to reimagine the concerto principle without a single soloist. The model drew on Baroque concerto grosso dialogue, the symphonic tradition’s large‑scale form, and the late‑Romantic fascination with orchestral color. Italian composer Goffredo Petrassi became pivotal from the 1930s onward, composing a renowned series of Concerti per orchestra that helped codify the genre’s identity as a display vehicle for the entire orchestra.

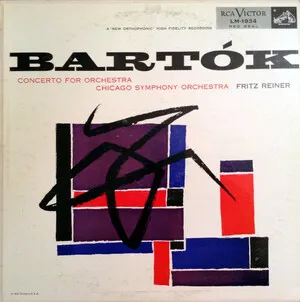

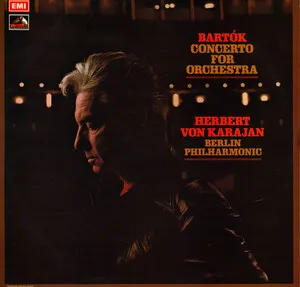

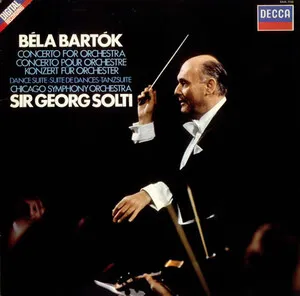

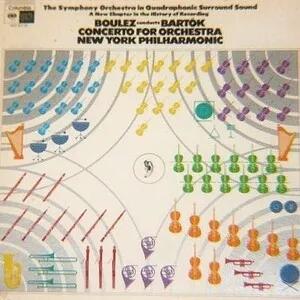

Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra (1943) popularized the genre internationally, combining folk‑inflected modality, rhythmic vitality, and brilliant sectional solos within an arch‑like design. In the postwar period, Witold Lutosławski’s Concerto for Orchestra (1954), with its folk‑derived materials and contrapuntal rigor, further cemented the form. Parallel contributions by Walter Piston, Michael Tippett, and Grażyna Bacewicz expanded the idiom’s harmonic language and formal possibilities.

Late 20th‑ and 21st‑century composers have used the concerto‑for‑orchestra idea as a flexible canvas for modern orchestral imagination. Steven Stucky (including a Pulitzer‑winning second concerto), Joan Tower, and Jennifer Higdon fused contemporary harmonic palettes, sharp rhythmic profiles, and virtuosic orchestration. Today, the genre continues to thrive as a concert‑hall showpiece, a proving ground for orchestral technique, and a bridge between historical forms and modern orchestral writing.

How to make a track in this genre

Use a full symphony orchestra (expanded winds, brass, percussion, and often piano/harp). Treat sections and principals as rotating soloists. Plan coloristic contrasts: soli woodwind choirs, antiphonal brass, string divisi, and exposed percussion writing.

Adopt multi‑movement designs (often 3–5 movements) or a large single span with internal sections. Common strategies include theme‑and‑variations, arch forms, or episodic sequences that spotlight different instrumental groups. Balance display movements with slower, lyrical panels to feature timbral nuance.

Employ a modern but lucid harmonic palette: extended tonality, modality, quartal/quintal chords, or symmetric collections. Ensure clear pitch centers when needed to articulate structure and keep solo passages audible. Use pedal points and harmonic plateaus to frame virtuoso episodes.

Favor propulsive, dance‑like rhythms, asymmetric meters, and metric modulation to energize transitions. Build episodes around ostinati or motor rhythms that allow intricate figurations and counter‑solos to interlock across sections.

Design virtuosic lines for every family—rapid string passagework, tongue‑twisting wind runs, bravura brass fanfares, and idiomatic percussion features. Use call‑and‑response and layered counterpoint to dramatize inter‑sectional “dialogue.” Keep registral spacing and dynamic terraces clear so concertante details project.

Write clear cues and balance markings for the conductor to manage quick spotlights. Plan rehearsal‑friendly textures: sectional soli, concise tuttis to reset balance, and orchestrational “breathing spaces” before complex showcases.

Top albums