Your digging level

Description

Chechen folk music is the traditional music of the Vainakh (Chechens and Ingush) from the North Caucasus. It blends heroic epic singing (illi), fast, high-energy dance tunes, and devotional Sufi zikr chants, creating a spectrum that runs from intimate, narrative song to communal, trance-like ritual.

Its sound world features modal melodies, heterophonic textures, and vivid rhythmic drive. Core instruments include the three‑string phandar (pondur) lute, zurna/oboe and other folk winds, frame drums (daf), and—since the 20th century—the accordion for dance sets. The style’s dance repertoire (including the local variant of the Caucasian lezginka) is characterized by tight 2/4 or 6/8 pulses, sudden accelerations, and stomping accents, while the epic and devotional repertories emphasize declamatory vocals, call‑and‑response, and refrain-based forms.

History

Chechen folk music arose from the Vainakh mountain pastoral culture as an oral tradition. Heroic epics (illi) were performed by specialist bards who combined narrative recitation with sung refrains, preserving clan histories, valor, codes of honor, and moral exempla. Melodic practice favored modal scales, narrow to medium ranges, and heterophonic group participation, with the phandar (pondur) lute accompanying vocal delivery.

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, Islam—particularly the Qadiri and Naqshbandi Sufi orders—deeply shaped local music-making. Zikr (dhikr) ceremonies introduced cyclic chanting, unison responses, drone-like tonal centers, and frame‑drum accompaniment, reinforcing a spiritual, communal ethos distinct from the secular dance and epic repertories.

Russian imperial ethnographers documented Chechen song and dance in the 19th century. In the Soviet period, staged folk ensembles professionalized the idiom: choreographed lezginka variants, polished vocal groups, and accordion-led dance suites became emblematic on radio and touring circuits. The Chechen-Ingush State Ensemble “Vainakh” popularized stylized versions of village repertoire while preserving key modal and rhythmic traits.

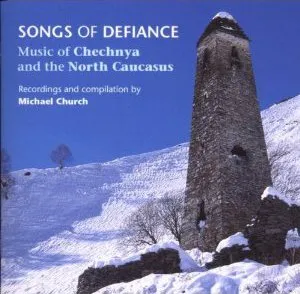

The 1944 deportation to Central Asia left deep marks on repertoire—laments and songs of exile proliferated, while community rituals helped maintain identity. After rehabilitation and return, local and diaspora artists revived epic and dance genres. Late-20th-century singer‑songwriters (including bardic voices) blended traditional modes and themes with new instruments and recording aesthetics.

Today, Chechen folk music lives across community rituals, staged ensembles, and recordings. Dance ensembles keep virtuosic forms vibrant; zikr circles continue devotional practice; and singers adapt illi and folklore themes into acoustic and folk‑pop formats. Despite modernization, the genre’s core markers—modal melody, heterophony, ritual participation, and dance-driven rhythm—remain intact.