Candombe beat is a Uruguayan fusion style that blends the Afro‑Uruguayan candombe drum tradition with 1960s beat/rock, soul, funk, and jazz harmonies.

It features the three traditional tambores (chico, repique, and piano) or their patterns emulated on drum set and percussion, layered under electric bass, guitar, vintage organs, and pop/rock vocals.

Emerging in Montevideo at the height of the Beatlemania era, it reframed local Afro‑diasporic rhythm within contemporary song forms, producing a distinctly Rioplatense take on rock and soul that is both groove‑centric and melodically rich.

With the global spread of beat music and rock in the mid‑1960s, Montevideo’s musicians began experimenting with ways to embed the local Afro‑Uruguayan candombe drum language into contemporary song forms. Bands and artist collectives around Eduardo Mateo and Rubén Rada—most notably El Kinto—pioneered a sound where the candombe drum battery (chico, repique, piano) interlocked with electric bass, guitar, and organ. The approach drew on the harmonic and melodic vocabulary of British‑influenced beat/psychedelia and North American soul and jazz while keeping the groove anchored in the neighborhood “llamada” feel of candombe.

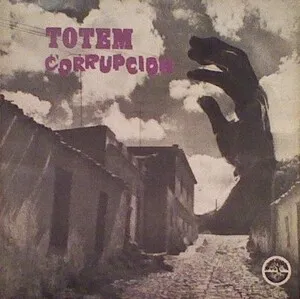

The early 1970s saw the style gain broader visibility through groups like Tótem and through the work of the Fattoruso brothers (Hugo and Osvaldo), who brought sophisticated arrangements and jazz‑inflected harmony to the idiom. The style’s calling card was its rhythmic identity: a two‑bar, clave‑like candombe pulse articulated by the three drums or by drum set/percussion, with bass lines that converse with the “piano” drum’s tumbling accents.

Following the 1973 civic‑military dictatorship in Uruguay, many musicians went into exile, scattering to Argentina, Brazil, and the United States. In this period, the candombe groove cross‑pollinated with jazz fusion via projects such as Opa, and artists like Rubén Rada continued to evolve the language abroad. Although commercial pressures and censorship constrained local production, the core aesthetic survived through live performance, recordings abroad, and a strong community of practitioners.

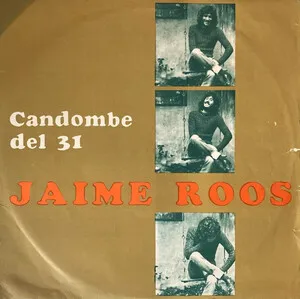

From the 1980s onward, artists such as Jaime Roos and Jorge Galemire helped re‑embed candombe beat in mainstream Uruguayan popular music, influencing generations of rock, pop, and jazz musicians. Reissues, archival projects, and contemporary bands have since renewed international interest, situating candombe beat as a key node in Latin American fusion—an Afro‑diasporic rhythm reimagined in song‑driven forms.