Cakewalk is a late-19th-century African American dance-music style marked by a jaunty, strutting feel in duple meter, syncopated rhythms, and march-like bass patterns.

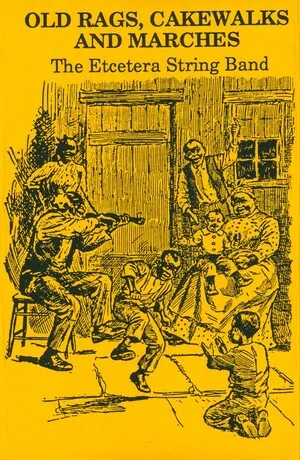

Originally accompanying competitive dances where a cake was awarded to the winning couple, its music typically features multiple 16-bar strains (often AABBCC or AABBACCDD), bright major keys, and catchy, syncopated melodies. It was performed by solo piano, banjo-led ensembles, and brass bands, and became a staple of minstrel and vaudeville stages before feeding directly into the emergence of ragtime and early jazz.

Cakewalk began among African Americans in the post-Civil War American South, evolving from plantation gatherings where dancers humorously parodied elite European ballroom manners. The winners were sometimes awarded a cake, lending the form its name. Musically, early cakewalks drew on the strong two-beat pulse of marches, the social-dance ethos of polkas and schottisches, and the showmanship of minstrelsy and brass bands.

By the mid-to-late 1890s, cakewalk had exploded in popularity on minstrel and vaudeville circuits and in urban parlors. Composers published piano and band cakewalks with multi-strain forms and crisp syncopations. Notable hits such as Kerry Mills’s "At a Georgia Camp Meeting" (1897) and Abe Holzmann’s "Smoky Mokes" (1899) circulated widely in print and on early recordings by banjo virtuosi and brass bands. On Broadway, Williams and Walker’s productions (with music by Will Marion Cook) brought the dance to mainstream audiences. The style’s reach was international—Claude Debussy famously wrote "Golliwogg’s Cakewalk" (1908), a classical homage to the idiom.

Cakewalks typically use a 2/4 meter with a firm two-beat "oom-pah" foundation, syncopated right-hand figures (on piano) or melody lines (in bands), and sectional designs modeled on marches (often with a contrasting "trio" strain). Keys are usually bright majors (F, B♭, E♭, C), with straightforward harmony colored by secondary dominants and simple modulations.

As ragtime, early jazz, and new social dances took center stage in the 1910s, cakewalk’s popularity waned. Yet its rhythmic vocabulary, multi-strain architecture, and dance-forward showmanship fed directly into ragtime and, through it, the language of early jazz, Dixieland, and novelty piano. The cakewalk remains a crucial link in the genealogy of American popular music and dance.