Schottische is a partnered social dance and tune type that emerged in mid‑19th‑century Central Europe and quickly spread across ballrooms and village dances.

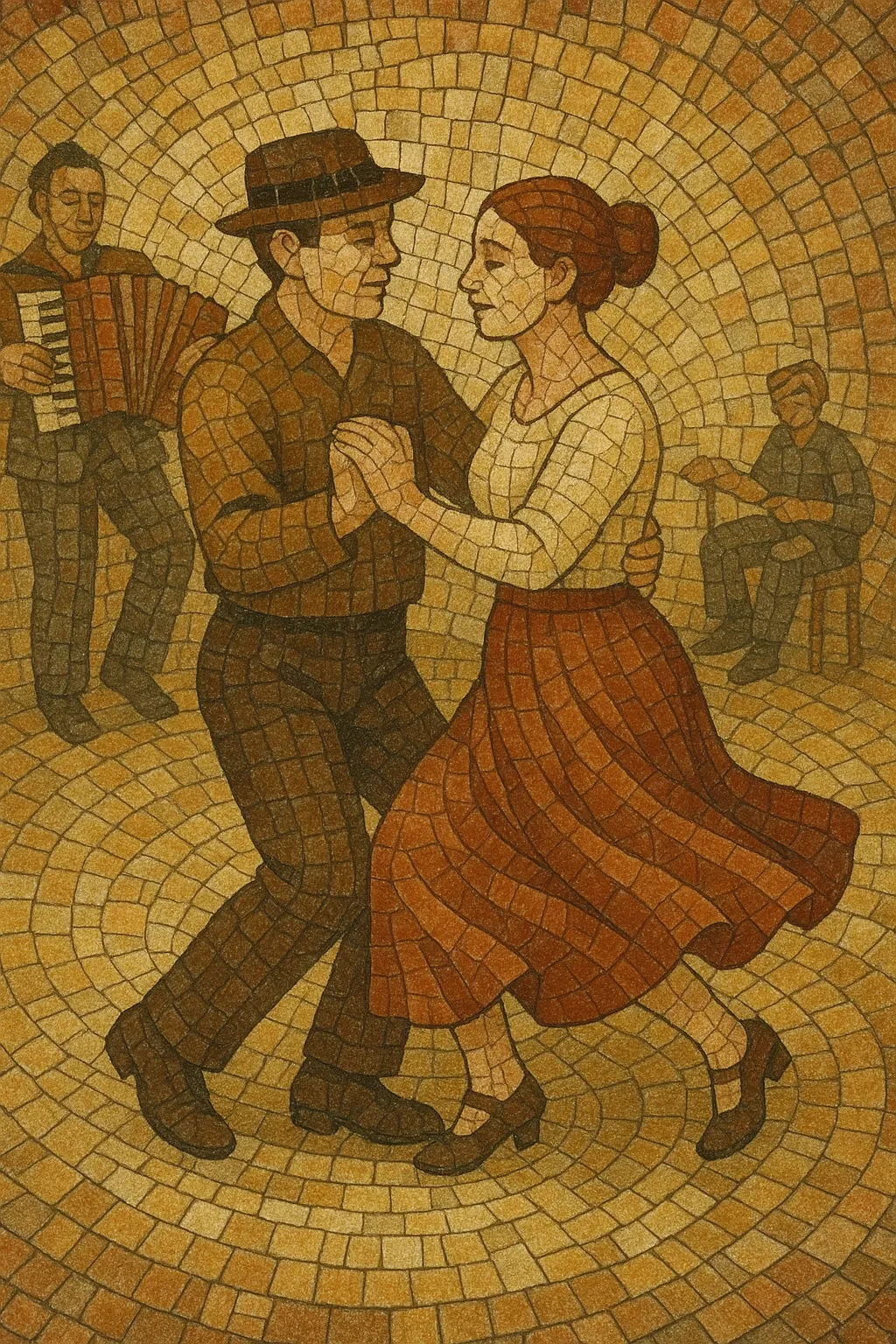

Typically in 2/4 (sometimes 4/4) at a moderate tempo, it features a characteristic step pattern (step‑step‑step‑hop) followed by a turning figure, creating a gentle, gliding feel. Musically, schottische tunes are usually built from two 8‑bar strains (AABB), use diatonic melodies in major keys, and are accompanied by a pronounced oom‑pah rhythm. Fiddles, diatonic button accordion, clarinet, piano, and small dance bands are common.

The dance took root under different names and flavors: as schottis in Scandinavia, chotis in Spain (especially Madrid), and xote in Brazil, where it entered the forró tradition.

The schottische arose during the mid‑19th‑century European dance craze that also popularized polka and other “German” dances. Despite its name (“Scottish”), most sources trace its formation to Central Europe (German‑speaking regions and Bohemia), entering fashionable ballrooms around the late 1840s.

From Central Europe the dance and its tunes traveled rapidly. In Britain and Ireland it joined the country‑dance repertoire; in Scandinavia it became the schottis; in Spain it became the chotis, particularly emblematic in Madrid. Its simple, catchy step and accessible musical form made it ideal for village bands and salon orchestras alike.

In the Americas, the schottische blended with local traditions. In Brazil it transformed into the xote and became a pillar of the northeastern forró scene alongside baião and arrasta‑pé. Quebec, the United States, and Mexico incorporated schottische (often labeled “barn dance” or “schottische”) into folk and old‑time repertoires.

Though fashions shifted, the schottische persisted in folk dance circles, Scandinavian spelmanslag (fiddlers’ ensembles), Scottish dance bands, Spanish cuplé/chotis traditions, and Brazilian forró. Folk revivals from the mid‑20th century onward helped sustain teaching, recording, and regional variants of the dance and its tunes.