Your digging level

Description

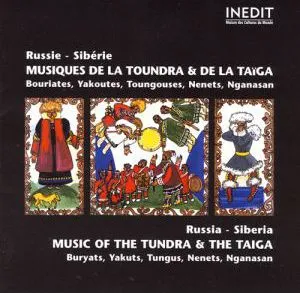

Buryat folk music is the traditional music of the Buryat people of Siberia, centered in the Republic of Buryatia (Russia) and bordering Mongolic regions. It blends ancient shamanic ritual song, epic recitation (uliger), Buddhist devotional elements, and steppe song traditions shared with Mongolian cultures.

Characteristic features include pentatonic melodies; long, melismatic vocal lines reminiscent of Mongolian “long song” practice; occasional overtone/throat-singing techniques; and the use of instruments such as the morin khuur (horse-head fiddle), khuuchir (spike fiddle), limbe (end-blown flute), jaw harp (khomus), frame drums, and various rattles used in ritual contexts. Social dance songs, notably for the yokhor circle dance, emphasize call-and-response and steady, communal rhythms.

Themes frequently celebrate the steppe, horses, kinship, and spiritual life, with lyrics that may invoke nature spirits in older shamanic pieces or reflect Tibetan Buddhist poetics introduced from the 18th century onward.

History

Buryat folk music emerges from the lived practices of the Buryat people, a Mongolic group in Siberia. Its oldest layers are linked to shamanic rituals—invocations, trance-inducing chants, frame-drum accompaniment, and call-and-response formulas associated with healing and community rites. Epic storytelling (uliger) and praise songs likely coalesced as distinct performance practices centuries ago, drawing on a shared steppe repertoire with other Mongolic groups.

From the 1700s, the spread of Tibetan Buddhism among the Buryats introduced monastic chant aesthetics and devotional song forms. While sacred chant remained institutionally separate, its modal thinking, vocal decorum, and poetic imagery bled into secular performance. Instruments such as the morin khuur and limbe gained broader prestige, and long, expansive melodies akin to Mongolian long song became emblematic of refined singing.

Under Soviet cultural policy, shamanic practice was curtailed, yet folk arts were curated into concert forms. State ensembles codified yokhor dance songs, work songs, and narrative ballads for stage, while ethnographers recorded elders and uligerchi (epic bards). This era standardized tunings, arrangements, and choir-style voicings, preserving core repertoires even as ritual contexts diminished.

Following the Soviet collapse, Buryat folk music experienced revivalism: renewed interest in shamanic heritage, community yokhor gatherings, and the emergence of professional artists who reintroduced jaw harp, throat-singing techniques, and traditional instruments. Contemporary acts tour internationally, fusing Buryat idioms with rock, ambient, and acoustic world-fusion, expanding the music’s audience while keeping its poetic and pastoral essence intact.