British trad jazz is the United Kingdom’s revivalist take on early New Orleans and Dixieland jazz, emphasizing collective improvisation, two‑beat feel, and repertoire drawn from blues, spirituals, rags, and early jazz standards.

Typically led by a trumpet–clarinet–trombone front line and supported by banjo or guitar, tuba or double bass, piano, and drums, the style prioritizes ensemble polyphony over long modern solos. It is earthy and danceable, projecting a cheerful, good‑time atmosphere while retaining the rustic, blue‑tinged phrasing of its New Orleans models.

The scene blossomed in late‑1940s/1950s London club culture and crested with a nationwide “trad boom” around 1960–1962, when bands led by Acker Bilk, Kenny Ball, Chris Barber, and others reached the UK pop charts.

In the aftermath of World War II, British musicians inspired by early New Orleans and Chicago jazz began reviving pre‑swing idioms. Humphrey Lyttelton formed a band in 1948, and London venues such as the 100 Club (on Oxford Street) became hubs for revivalist jam sessions, traditional repertoire, and social dancing.

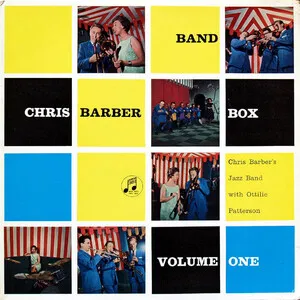

During the 1950s, bands codified a distinctly British revivalist approach: collective front‑line improvisation (trumpet, clarinet, trombone), a strong two‑beat feel, repertoire of rags, spirituals, blues, marches, and early standards, and rhythm sections often featuring banjo and tuba. Ken Colyer’s pilgrimage to New Orleans and his Jazzmen, Chris Barber’s Jazz Band, and Humphrey Lyttelton’s early groups became touchstones. The scene also fostered skiffle—via Barber’s band with Lonnie Donegan—which would later shape British popular music more broadly.

Around 1960–1962, trad jazz crossed into mainstream pop. Mr. Acker Bilk (“Stranger on the Shore”), Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen (“Midnight in Moscow”), Terry Lightfoot, Monty Sunshine, and the tongue‑in‑cheek revivalists The Temperance Seven all enjoyed hit records and TV exposure. The music’s upbeat, communal energy aligned with social dancing and youth club culture.

The Beat Boom and the rise of rock in 1963–1964 eclipsed trad’s chart presence, but the style persisted through club circuits, festivals, and dedicated societies. Chris Barber’s advocacy brought American blues artists to UK audiences, linking the trad scene to the burgeoning British blues movement. Today, British trad jazz continues as a vibrant live tradition, sustaining the repertoire and ensemble practices of early jazz for new generations of listeners and dancers.