Breton Celtic folk music is the dance-centred traditional music of Brittany (Breizh) in north‑western France, rooted in the Breton language and the wider pan‑Celtic soundworld. It revolves around fest‑noz social dances, call‑and‑response singing (kan ha diskan), narrative laments (gwerz), and driving instrumental sets designed to keep long chains of dancers moving.

Typical instruments include the bombarde and biniou kozh (Breton bagpipe), Celtic harp, diatonic accordion, fiddle, and later guitar and bouzouki; modern ensembles may also feature the Scottish Great Highland bagpipe (binioù bras) and snare drum under the influence of bagadoù (Breton pipe bands). Melodies are largely modal (Dorian, Mixolydian, Aeolian), drone‑based, and strongly rhythmic, serving specific dance types such as an dro, hanter‑dro, gavotte, plinn, laridé/ridée and others in metres from 2/4 and 4/4 to 6/8 and 12/8.

While deeply traditional, the genre has continually refreshed itself through revivals and cross‑Celtic exchange, informing contemporary Celtic rock, Celtic electronica and global “world music” stages.

Brittany’s song and dance traditions reach back centuries through oral transmission in Breton (a Brythonic Celtic language) and Gallo. Ballads (gwerzioù) and dance songs (sonioù) were collected in the 19th century, most famously in the anthology Barzaz Breiz (1839), which helped codify awareness of a distinct Breton repertoire even as the French state discouraged regional languages.

After World War II, cultural associations and fest‑noz organisers spearheaded a folk revival. Loeiz Ropars is often credited with revitalising fest‑noz formats, placing kan ha diskan and dance sets back at the music’s centre. In parallel, the bagadoù (pipe‑band) movement emerged via Bodadeg ar Sonerion (founded 1943), adapting Scottish pipe‑band instrumentation to Breton marches, an dro and gavottes.

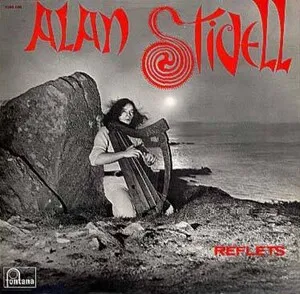

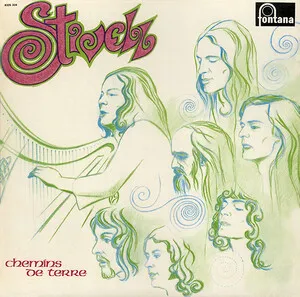

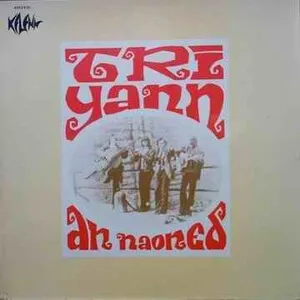

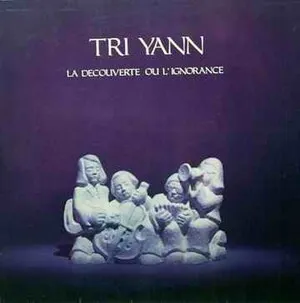

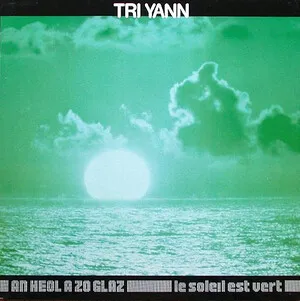

The late 1960s–1970s brought a pan‑Celtic and folk boom: Alan Stivell modernised the Celtic harp and popularised Breton music internationally; Tri Yann, Dan Ar Braz and others blended traditional melodies with contemporary folk/rock arrangements. This period cemented “Breton Celtic folk music” as both a living dance tradition and an exportable Celtic identity.

Festivals such as the Festival Interceltique de Lorient connected Brittany to Irish, Scottish, Welsh, Galician and Asturian scenes. Artists like Yann‑Fañch Kemener and Denez Prigent brought vocal traditions to new audiences, sometimes fusing them with ambient, electronic and global textures, while bagadoù rose to competitive prominence.

Breton Celtic folk thrives in local fest‑noz circuits and on international stages. Dance bands (e.g., Sonerien Du, Ar Re Yaouank) maintain high‑energy sets for social dancing, while singers and instrumentalists continue to explore both historically informed performance and hybrid forms with rock, electronica and world fusion.