Bamar folk music is the traditional music of the Bamar (Burman) people, the largest ethnic group of Myanmar. It centers on expressive vocals, cyclical rhythms, and a distinctive heterophonic texture in which multiple instruments elaborate the same melody with different ornaments.

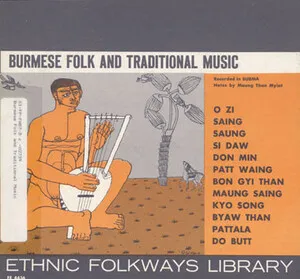

Typical ensembles range from intimate combinations of voice, Burmese arched harp (saung gauk), and small percussion to the vibrant hsaing waing, a gong-and-drum orchestra featuring pat waing (drum circle), kyi waing (gong-chime), maung hsaing (suspended gongs), hne (double-reed shawm), and the si/wa bell-and-clapper pair. Melodies draw on pentatonic and heptatonic frameworks with nuanced microtonal inflections, while performance practice includes extensive ornamentation, flexible phrasing, and call-and-response. The music accompanies seasonal festivals (such as Thingyan), spirit ceremonies (nat pwe), puppet and dance-theatre (yoke thé and anyein), and everyday social life.

As a living folk tradition, Bamar music balances devotional, satirical, celebratory, and narrative functions. Lullabies, work songs, festival tunes, and poetic song forms sit alongside ceremonial repertories whose rhythms and modal contours are shaped by Theravāda Buddhist aesthetics and regional Southeast Asian gong-chime idioms.

Bamar folk music traces its roots to the Pagan (Bagan) period (11th–13th centuries), when courtly arts, Buddhist liturgy, oral poetry, and community ritual intersected. Early song practices coexisted with spirit (nat) veneration, creating a repertoire that moved fluidly between sacred and secular settings. Instruments such as the saung gauk (arched harp) and idiophones appear in early iconography and chronicles.

Across subsequent dynasties (Ava, Taungoo, Konbaung), a two-way exchange blossomed between folk practice and courtly/classical music. Court ensembles codified rhythmic cycles and modal organization, while village traditions contributed melodic turns, texts, and performance styles. Regional contact with Mon, Shan, and Khmer/Thai gong-chime cultures reinforced the hsaing waing aesthetic—layered, cyclical, and ornament-rich.

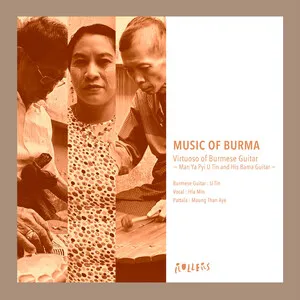

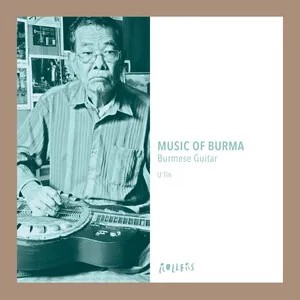

Under British colonial rule, urban centers fostered new stages (theatre, anyein pwe, and yoke thé puppet troupes) that popularized folk repertoires. Early 20th-century composers and bands (notably around Mandalay) adapted festival and ceremonial pieces for public performance. After independence (mid-20th century), radio and recording helped standardize and disseminate folk songs nationwide while preserving village variants.

Today, Bamar folk music remains integral to festivals (e.g., Thingyan), nat ceremonies, and community events. Revivalist musicians and cultural troupes maintain traditional instrumentation and vocal styles, while modern interpreters blend folk idioms with popular, acoustic, or ensemble arrangements for concert stages and media, ensuring continuity of the core melodic language, heterophony, and ritual functions.