Balkan folk music is a pan‑regional set of traditional styles from the Balkan Peninsula, spanning Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Romania (southern regions), Greece, Albania, Montenegro, Croatia (inland), and the European part of Türkiye.

It is characterized by asymmetric “aksak” meters (such as 7/8, 9/8, 11/8), richly ornamented melodic lines derived from modal systems, close two‑part vocal harmonies (often with pungent seconds), heterophonic textures, and powerful dance grooves. Common instruments include gaida (bagpipe), kaval (end‑blown flute), gadulka (bowed lute), tambura/tamburica and saz (long‑neck lutes), tapan/daouli (large double‑headed drum), darbuka, zurna, clarinet, accordion, fiddle, and brass band instruments.

Songs and dances (horo/oro/kolo/čoček) accompany weddings, seasonal rites, and village festivities, while urban styles like sevdalinka embody a more lyrical, melancholic strand. The music’s sound world blends Byzantine and Ottoman legacies with Slavic, Greek, Albanian, and Romani (Gypsy) traditions.

The Balkans served for centuries as a cultural crossroads between Europe and West Asia. Rural music developed around communal dances, ritual calendars, and epic or lyrical song. Modal practice echoes Byzantine chant and Ottoman maqam traditions, while village instruments (gaida, kaval, tambura) shaped local timbres.

From the 14th to the 19th century, Ottoman rule facilitated transmission of melodic modes, rhythmic cycles, and instruments (zurna, darbuka, saz). In the 1800s, national revivals and early folklorists began collecting and notating village repertoires, fixing regional dance types (horo, kolo, oro) and vocal styles into recognizable “national” canons.

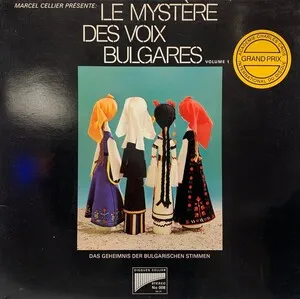

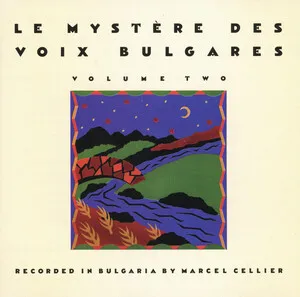

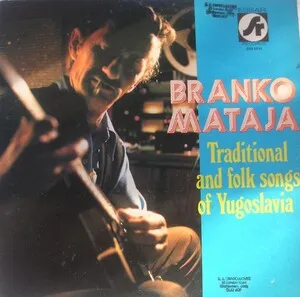

Radio, recording, and urbanization professionalized folk performance. State‑sponsored ensembles and choirs (e.g., in Bulgaria and across former Yugoslavia) arranged village tunes for stage, popularizing close harmonies and complex meters worldwide. Urban song traditions such as Bosnian sevdalinka crystallized, while Roma musicians became central to wedding and festival circuits, fueling virtuosic clarinet, violin, and brass band styles.

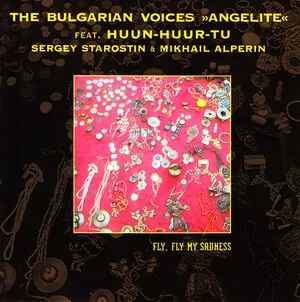

Late 20th‑century “world music” audiences embraced Balkan brass, Bulgarian women’s choirs, and sevdah singers. Post‑1990s, artists blended folk with rock, jazz, pop, and electronic music, inspiring genres like turbo‑folk, Balkan pop‑folk, and global brass band revivals. Today, the tradition thrives both in local celebrations and on international stages, balancing preservation with inventive cross‑genre fusion.