Macedonian folk music is the traditional music of North Macedonia, known for its rich vocal styles, modal melodies, and distinctive asymmetrical rhythms (aksak). It is performed for weddings, seasonal rituals, and village dances (oro), and it preserves regional dialects and stories in the Macedonian language.

The sound is shaped by a blend of Slavic, Byzantine, and Ottoman cultural layers. Typical instruments include gaida (bagpipe), kaval (end-blown flute), tambura (long‑necked lute), zurla (shawm), and tapan (large double‑headed drum), with later additions such as clarinet, accordion, and violin. Vocal music ranges from powerful solo laments to antiphonal and heterophonic group singing with a sustained drone (ison) reminiscent of Byzantine practice.

Rhythm is central: dancers and musicians favor meters such as 7/8 (3+2+2), 9/8 (2+2+2+3), 11/8, and 13/16. Ornamented melodies (slides, turns, trills) often sit in Dorian, Aeolian, or Mixolydian colors, and occasionally use maqam-like intervals (augmented seconds) inherited from Ottoman aesthetics.

The foundations of Macedonian folk music lie in rural ritual and dance traditions that predate the 19th century, when the region was part of the Ottoman Empire. Village ensembles of zurla and tapan accompanied circle dances (oro), while epic songs, harvest tunes, and wedding repertoires circulated orally across mountain and valley communities.

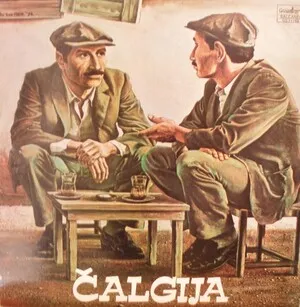

During the 1800s and early 1900s, teachers, priests, and early folklorists began documenting local songs and dance melodies. Urban salons developed chalgija (urban folk) variants alongside village styles, reflecting a synthesis of Slavic, Byzantine, and Ottoman musical vocabularies.

After World War II, the Socialist Republic of Macedonia (within Yugoslavia) created cultural institutions that codified and popularized folk arts. The national ensemble Tanec (founded 1949) arranged village materials for stage, toured internationally, and helped standardize instrumental line‑ups. Radio Skopje sessions, conservatory training, and national festivals brought master performers (singers, gaida and kaval players, clarinetists) to wider audiences.

Following independence in the 1990s, revivalists, Roma brass bands, and crossover artists brought Macedonian rhythms and melodies to world‑music circuits. Iconic songs such as “Jovano Jovanke” and “Zajdi, zajdi” gained new life in concert halls and recordings. Contemporary projects blend folk timbres and meters with jazz, pop, and electronics while community ensembles and festivals continue to sustain regional dance and singing traditions.

%2C%20Cover%20art.webp)