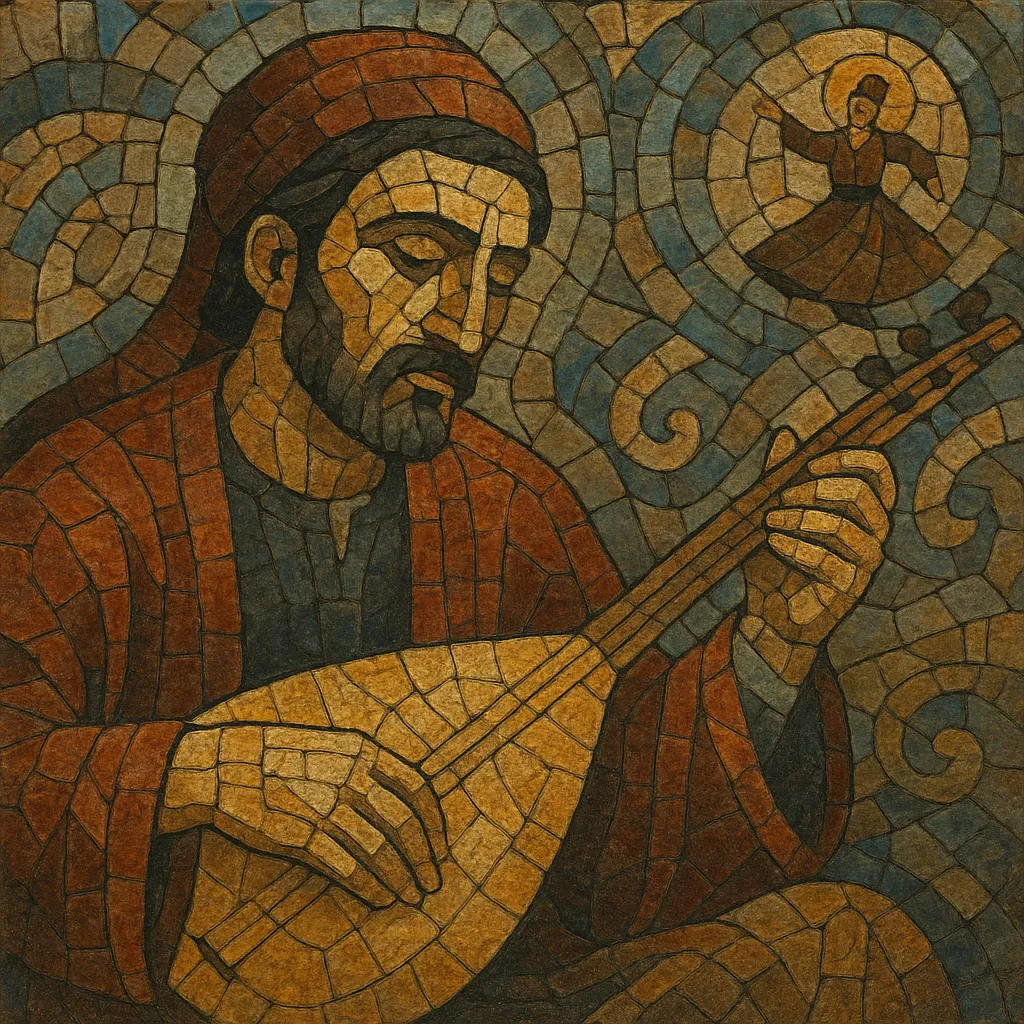

Alevi folk music (Alevi–Bektaşi music) is the devotional and vernacular song tradition of the Alevi communities of Anatolia. It is centered on the bağlama (saz) and the sung poetry of the âşık/ozan lineage, conveying mystical, ethical, and communal teachings.

Core forms include deyiş and nefes (didactic, mystical hymns), düvaz-ı imam (praise of the Twelve Imams), and semah (songs accompanying the ritual turning/dance). Melodies often draw on folk-modal practice related to the Turkish makam world, while rhythm favors both free-meter recitation and asymmetrical “aksak” cycles such as 5/8, 7/8, and 9/8. The performance practice is intimate and participatory, with a zakir (lead singer/bağlama player) guiding congregational response during the cem ritual.

Alevi folk music crystallized around the poetry and ritual life of heterodox Anatolian communities from the late medieval to early modern period. The mystical humanism of Yunus Emre (13th–14th c.) and the explicitly Alevi/Bektaşi poetry of Pir Sultan Abdal and Şah İsmail Hatayi (16th c.) supplied much of the canonical text repertoire. These poems were sung to the bağlama in village gatherings and the cem ceremony, embedding doctrine and ethics in accessible musical form.

From the Ottoman era onward, the âşık/ozan tradition transmitted repertory, technique, and worldview. The bağlama family (cura, tambura/divan saz) became the emblematic instrument, with characteristic tunings (bağlama/bozuk/kara düzen) supporting drones and modal contours related to folk adaptations of makam.

In the Republican period, field collectors and radio archives began documenting regional repertoires. Artists such as Âşık Veysel, Ali Ekber Çiçek, and later Arif Sağ and Musa Eroğlu brought Alevi songs to national audiences while preserving ritual contexts. From the 1970s, urbanization and cassette culture amplified circulation; Alevi poetry also intersected with socially conscious currents, shaping contemporary performance aesthetics.

Today, Alevi folk music is heard both within the ritual space (cem houses) and on concert stages. Conservatories teach bağlama technique; ensembles explore polyphonic arrangements while maintaining the primacy of voice-and-saz delivery. The tradition continues to evolve through Kurdish/Zaza and Turkish-language repertoires, new compositions in the style of nefes and deyiş, and collaborations with folk, world, and Anatolian rock scenes.